Reread, actually, the other night.

The Malacia Tapestry by Brian W. Aldiss. Harper & Row, 1977 (1976 for the UK first edition).

I became aware of Aldiss’s imaginary city-state of Malacia in excerpts originally published in Damon Knight’s Orbit 12 (1973). When the actual novel’s US edition first came out, I read a library copy right away. For many years I owned an Ace Books paperback reprint with the amusingly godawful cover painting by Rowena (I think—she was big in the seventies) shown in the second image below. I believe the book is out of print, in this country anyway, which is a damn shame, but I picked up a not-too-badly used first US edition hardcover from eBay or Amazon or somewhere a couple years ago. Thankfully, the dustjacket reproduces two of the G.B. Tiepolo etchings that seem to have inspired the novel, but this image seems to be the UK edition: the typography’s slightly different and that’s not Harper & Row’s logo on the spine.

It’s a very odd book and Malacia is a very odd place. Aldiss is not known for the rigor or consistency of his science-fictional or fantastical world building (except perhaps in the Helliconia trilogy, which I now want to reread as well), but even by Aldissian standards Malacia is a nonsense. Which is fine, actually, once you get past expecting something called a Bucintoro to be a Venetian ceremonial galley instead of a gold-paved river wharf, or for Constantinople to be Ottoman in what seems to be a perpetual eighteenth century, not still Byzantine.

It’s a very odd book and Malacia is a very odd place. Aldiss is not known for the rigor or consistency of his science-fictional or fantastical world building (except perhaps in the Helliconia trilogy, which I now want to reread as well), but even by Aldissian standards Malacia is a nonsense. Which is fine, actually, once you get past expecting something called a Bucintoro to be a Venetian ceremonial galley instead of a gold-paved river wharf, or for Constantinople to be Ottoman in what seems to be a perpetual eighteenth century, not still Byzantine.

It’s also an odd book because one simply expects “a major work of speculative fiction” published in the 1970s to be almost anything (thrilling adventure story, probably, or austere futurism) but a baggy, episodic if not quite picaresque Bildungsroman that concludes with a rousing call to class warfare. In 2014, I found the final pages (which I’d totally forgotten) refreshing and strangely on point.

Malacia was founded millions of years ago (nonsense!) with a curse from its founder that it should always remain the same. Its citizens are convinced they are descended from ancestral animals—dinosaurs (not the dragons Rowena wants you to believe)—which, though rare, still roam the nearby forests or are displayed in aristocrat’s menageries or hunted in their private parks. Citizens of other nations may have evolved from apes, but that just goes to show how inferior they are. Eternally threatened by the savage Turks just over the mountains, the Malacians live an endless round of decadent pleasures, entertained by the local satyrs and the winged people who perch on their cathedral and palace spires—very much in line with the last century or so of the Venetian Republic’s existence. Except for the satyrs and winged people, of course.

Our hero and narrator, Perian de Chirolo, is a down-at-the-heels young actor, raconteur, and lothario, very sure he is the pinnacle of Malacian civilization, until he has the misfortune of falling in love with the bewitching daughter of a wealthy merchant. Marriage is of course out of the question, though Perian spends a great deal of time persuading himself otherwise…when he isn’t making love to her in all the myriad ways that will maintain her virginity and marketability. Or seducing her best friend. Or the wife of the theatrical entrepreneur who occasionally employs him. Or sundry other lasses.

I must say—I will say—that the relentless heterosexual intrigue of this novel grows a bit wearying for this gay male reader, although one puts up with it for the sake of other delights. [Sidebar: Why is that so very many vocal straight male readers are incapable of the opposite feat when faced with fiction involving gay people? A puzzle for the ages.] Oddly, though, Perian and his jolly companions read as stereotypical artsy, frivolous, promiscuous theater-fags rollicking from bar to love affair to theatrics to parades, despite all the affairs being with winsome (but busty) young ladies. There is one (one) piece of evidence that not all citizens of the grand metropolis of Malacia are straight: a reference to “fancy-men” taking communion in the cathedral with their boys’ semen still sliming their hands.

In the end, the only work I can think of remotely comparable to the mostly forgotten (unjustly) Malacia Tapestry is Mervyn Peake’s more-discussed-than-read Gormenghast trilogy—which has just gone on my to-be-reread-right-fast list. Where the surface textures of Titus Groan et seq. are deadly serious, The Malacia Tapestry’s are farcical and frivolous, but the underlying worlds and themes are oddly similar, as if Aldiss had turned a rose-colored kaleidoscope on the ancient massif of the Groans’ immemorial castle.

(Oh, wait. Just before I hit publish I remembered Michael Moorcock’s Gloriana; or, The Unfulfill’d Queen, which Moorcock has acknowledged as his homage to Peake, and which stands to the monolith of Gormenghast at a similar—slightly more ribald—angle as The Malacia Tapestry. But Gloriana was first published two years after the Tapestry so if there’s any influence between them it went the other way.)

Also read/reread within the last couple weeks:

The Ladies of Grace Adieu, and other stories by Susanna Clarke. Bloomsbury, 2006.

This was a first read—strangely, since I bought the book in 2006, I believe, still under the spell of Clarke’s first book. Or maybe I read a few pages then and realized what my ultimate verdict would be, so set it aside. That verdict is: I don’t feel Clarke writes successful short(ish) stories. Lord knows Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell is a majestic, terrifying, and nearly perfect novel which I adore without reservation, but many of the techniques that worked to tremendous effect in that monstrous tome fall flat in a shorter piece. Grace Adieu is arch where Jonathan Strange was witty, trivial where the novel was transcendent—it seems always to be patting itself on its back and telling itself how clever it is. (Also, I hate, hate, hate Charles Vess’s illustrations.) Still, Clarke’s vision of Faerie and its inhabitants remains disturbing and beautiful.

This was a first read—strangely, since I bought the book in 2006, I believe, still under the spell of Clarke’s first book. Or maybe I read a few pages then and realized what my ultimate verdict would be, so set it aside. That verdict is: I don’t feel Clarke writes successful short(ish) stories. Lord knows Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell is a majestic, terrifying, and nearly perfect novel which I adore without reservation, but many of the techniques that worked to tremendous effect in that monstrous tome fall flat in a shorter piece. Grace Adieu is arch where Jonathan Strange was witty, trivial where the novel was transcendent—it seems always to be patting itself on its back and telling itself how clever it is. (Also, I hate, hate, hate Charles Vess’s illustrations.) Still, Clarke’s vision of Faerie and its inhabitants remains disturbing and beautiful.

Kingdoms of Elfin by Sylvia Townsend Warner. Viking 1977. My copy is the 1978 Delta paperback with the stupidly Genre!Fantasy! cover pictured below, bought used at Powell’s in Portland, OR, quite a few years ago. (When I still had disposable income for travel and books.)

A first read, although I’d been aware of and vaguely interested in the book nearly thirty years by the time I picked up a copy and…didn’t read it. Until now.

A first read, although I’d been aware of and vaguely interested in the book nearly thirty years by the time I picked up a copy and…didn’t read it. Until now.

Stories about fairies first published in The New Yorker—what a peculiar thing. They’re not your typical New Yorker stories, that’s for sure. Nor your typical fairy stories. They are very well made, though, as you’d expect of stories that went through that magazine’s editorial mill. I…am not quite certain how I feel about them. I didn’t especially enjoy them—there are no living, breathing characters, human or fairy, just attitudes and philosophical positions in the shapes of men (and fairies)—nor did I find Townsend Warner’s vision of the elfin kingdoms magical, convincing, or (fatally) novel. But I admired them a great deal and don’t at all regret reading the book.

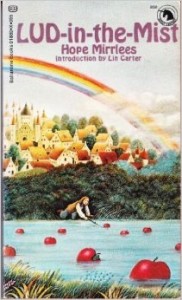

Lud-in-the-Mist by Hope Mirrlees. Collins (London), 1926. My (current) copy is a poorly proofread 2005 Cold Spring Press reprint, bought used at Powell’s and possessed of a grotesquely inappropriate and not very well done, uncredited cover painting. But the first copy I owned and read was the 1970 Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series paperback (issued without the author’s consent or knowledge because Ballantine couldn’t track her down—she died in 1978) with the delightful Gervasio Gallardo (I think) cover below.

Like the Gormenghast trilogy, an acknowledged classic more discussed than read, despite the best efforts of Michael Swanwick. Although in nearly every other way (aside from an inescapable Englishness) you couldn’t find a work more different than Peake’s grotesque monument. Actually, I think you might productively compare it to Peake’s Mr Pye, which, alas, is hardly discussed at all. Maybe it’s the coziness and apparently banal ordinariness of the eponymous town and its upright burghers that scares contemporary readers off. Maybe it’s the middle-aged-dad protagonist—no dashing young hero here for poorly socialized Xbox nerds to take as their avatar. Whatever. It’s a mostly quiet and good-humored petit-bourgeois novel layered atop a truly peculiar and ultimately frightening vision of Faerie, the world beyond the hill, and an eccentric masterpiece.

The last three titles should make it obvious I am interested in Faerie and fairies these days. Next on my to-reread list is Lord Dunsany’s The King of Elfland’s Daughter, once the inter-library loan comes through. There are Reasons. Writerly Reasons. Of which more another time.