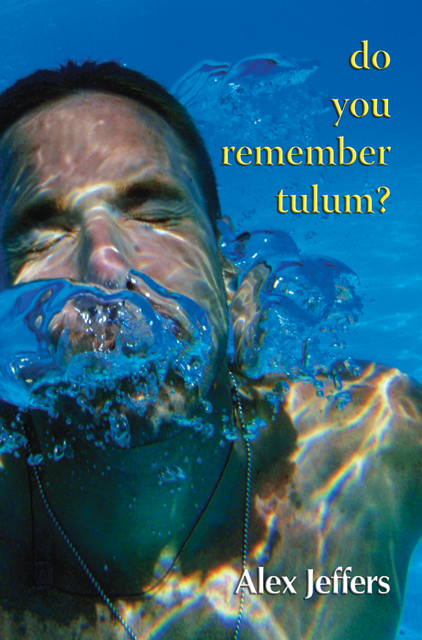

Novella in the form of a love letter.

“All they who love not tobacco and boys are fools.”

—attributed to Christopher Marlowe

Quintana Roo, 22 April 1988

Dear Ethan,

Years ago, long before we knew each other, querido, I used to write postcards to people I’d never met. I would tell them everything that happened to me, every accident and embarrassment, illness or surprise – like a diary, in a way, except that after filling out the message side of the card I’d invent a plausible-sounding name, choose a street address from the ZIP-Code Directory, and drop my message through the slot. I always signed them Hugs from Alex. I’m sitting here thinking about those scores of cards, hoping this letter will be as useful to me on my own terms but also that it won’t be so singular, so futile an exercise. I will at least put a return address on the envelope although I don’t know how much longer I’ll be here.

In early 1977, in search of adventure and exotica to fuel his fiction, a callow young would-be novelist from California relocated to the small southern Mexican town that gives the ancient Maya city-state of Palenque its modern name. A few months into his residence, he was visited by his absentee boss, a prep-school teacher, and ten of her students on spring break. Among those youths come to explore Palenque and other sites of the Maya lowlands were darkly magnetic Peter and sly, secretive Keenan. Over the next few weeks, travelling from Palenque to the Yucatán coast and back, Peter and Keenan would overturn the writer’s comfortable expatriate life and make him question everything he knew about love.

Eleven years later, the writer returns to Mexico on a spur-of-the-moment memorial trip. At Tulum above the blue Caribbean, he begins a letter to his boyfriend back in Boston to explain his abrupt, inadequately explained departure. Over five days and some seventy handwritten pages, he revisits the dramatic events of that earlier trip and, one eye always on the future, tries to understand and explain how a confused and frightened youth became a man capable of love.

Edmund White called Alex Jeffers’s Safe as Houses “a novel as complex as humanity about how to wrest decency and love out of uncertainty,” and the Lambda Book Report praised it as a book “about living, finding ways to define one’s life and one’s loves, about breaking rules to create new ones.” Do You Remember Tulum?, fiction in the form of a love letter, takes Jeffers’s exploration of love and the limits of decency in extravagant new directions. A dizzying travelogue, Do You Remember Tulum? maps the geographies of guilt, regret, hope, desire, and the deep roots of love.

Whenever I interview a writer, I always ask what book he or she has read by another author that they wish they had written. Well for me, Do You Remember Tulum? is the book I wish I had written. It is a novel, yet it is beautifully written in the form of a lengthy and delightful love letter. The prose is some of the loveliest and most moving that I have read. It gave me the feeling of voyeurism, that I was secretly reading someone’s letter to his lover, with all the passion and intimacy of two people deeply in love. And through this letter, this peeking into the narrator’s experiences, hopes, and dreams, I watched him map the geography of love.

—Alan Chin, Rainbow Reviews

My second book. Short story: Originally drafted between 1988 – 1990, simultaneous with the first draft of Safe as Houses. Not long enough to be of interest to commercial publishers of the period. After two decades in the trunk, self published in 2009 just to clear one deck. Recently reissued in more widely available (presumably more legitimate) form by my friends at Lethe Press. Long story follows.

For some interminable period in the mid-nineties after publication of Safe as Houses, a book-length manuscript entitled Selected Letters (Ethan’s Book) bounced from editorial desk to editorial desk in Manhattan and other esoteric places. My agent forwarded the rejection letters to me. The tenor was predictable. He writes beautifully (I paraphrase from memory), some of it’s very involving and affecting and impressive, but it’s not a novel (the manuscript was clearly, unironically subtitled NOT A NOVEL) and we can’t quite picture an audience, let alone a marketing plan.

What Selected Letters was (not a novel) was a collection of four fictions in the form of love letters to my imaginary boyfriend plus a final fictive letter to one of my real friends about said imaginary boyfriend. There was no through-narrative (what teevee writers call, I gather, a story arc) to hold the letters together, make them a book, and I never put any effort into reconciling minor inconsistencies between the letters. Indeed, it wasn’t till two thirds or three quarters into the fourth that I had any notion of gathering them together. Aside from the last, none was particularly concerned with the here-and-now—July 1985 through October 1993—or the on-going incidents and conduct of the love affair. Generally they were more interested in the past: my actual past in some instances (unless you are a very close friend who pries, maybe not then, you’ll never know) or events, occurrences, stories that might have, could have, should have happened if any writer’s life were as interesting as his imagination.

Letter the first

“A Man of the Future, A Man of My Dreams”

I drafted “A Man of the Future, A Man of My Dreams” in the spring and summer of 1985, more or less simultaneously with “Saying Grace” (see stories; scroll down to 1987) and like that story it falls squarely in what I’ll now formally label the Interior Décor Period of my writing. The endless descriptions of rooms and their furniture! Yow.

The first half of that year, I was pulling everything together to uproot myself from ancestral stomping grounds on the Monterey Peninsula to move to San Francisco (the letter’s dateline is its first lie). At the time, I failed entirely to understand autobiographical fiction—its appeal to writer (isn’t making things up the fun part?) or reader (isn’t its being made up what’s interesting?) (I’m not so much a fan of memoir or straight autobiography either)—or in truth that it was so very prevalent. Despite inclusion of the antique Chinese altar table that now serves as my desk (at which I’m typing now) and both my cats, “A Man of the Future” was not autobiographical. In real life, from force of habit, I was still going by the given name I’d been saddled with at birth, much as I hated it: the signature at letter’s end was a lie as well. “Alex” was merely a by-line who didn’t yet share a surname with me. “Alex” may have had a maternal first cousin named Ethan who lived in Boston but I did not—my mother’s only sister never left Detroit. “Alex” may have already been living in San Francisco with plans in train to relocate cross-country to Massachusetts, but my immediate goal was the foggy city by the bay, city of my dreams. Boston was a distant, only vaguely plausible prospect.

“A Man of the Future” remains conceptually interesting to me although I think it fails as story. During Selected Letters’s protracted existence as a book-length manuscript, I often considered dropping the first letter. Most every good point it makes is made better in other letters. It does not, I suspect, much encourage the reader to persevere. I preserve it here, I suppose, mainly on archival impulse.

Letter the second

Do You Remember Tulum?

I finally got to New England in the fall of 1987. Not Boston, not yet. I enrolled as a returning-adult undergrad at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. Taking advantage of the three thousand miles between me and everybody who knew me by my birth name, I introduced myself as Alex and meant it. (Two decades later, although I’ve never got around to formally, legally changing my name, I still mean it. I startle and flinch when family and old California acquaintances forget and address me by the old name.)

Spring semester of 1988, I entered a creative-writing workshop led by John Hawkes. I didn’t really know Jack’s work. The little I’d read, in prep, over winter break, didn’t agree with me—I no longer remember quite why. After he savaged, in a very low-key, civilized way, the chapter of my then-in-progress (never to be finished) novel I submitted to the workshop, it appeared my work didn’t agree with him either. I resolved to show him.

I wrote “Cartography” (see stories; scroll down to 1998), a fierce little story, trying to keep in mind the small part I understood of Jack’s objections to conventional narrative fiction (“the true enemies of the novel [are] plot, character, setting and theme”). Jack claimed to like it quite a lot. I didn’t, so much.

But “Cartography” had been written, deliberately, to appeal to Jack. Next, I resolved to write something that satisfied my requirements for fiction yet that would still startle and engage him. For another, more formal course, I was reading Samuel Richardson’s extraordinary Clarissa (a novel I felt sure Jack Hawkes must have loathed), so epistolary fiction was on my mind. In “Cartography,” for the first (probably last) time, I had used the house and town where I grew up as setting, so my mind was already inclined as far as it ever is toward autobiography. I recalled “A Man of the Future.” There you go: Character. Setting: I had never made good use in fiction of the landscapes of southern Mexico, the Maya areas of Chiapas state and the Yucatán, where I had lived for eighteen vivid months, 1977 – 1978. (For the record, I have yet to return.) Plot: I’d make it up! Something exciting and melodramatic—something to rival the plots of the gothic romances I’d read in Mexico for lack of any other English-language fiction! Theme could take care of itself.

I’m far from the first to write fiction that pretends to be autobiography, in which narrator pretends to be author while author invents every significant incident and motivation. Off hand, I think of Anton Shammas’s lovely Arabesques and David Leavitt’s novella “The Term Paper Artist” (in Arkansas). I’m not so sure, though, I knew it at the time. The first draft of the second letter to my imaginary boyfriend—then titled “Words for Today, Words for Tomorrow” in imitation of the strophe-antistrophe title of the first—was a shortish story, twenty-five or thirty pages, in which Ethan scarcely figured except as unwitting audience. I recalled a spectacularly beautiful young man who had been a sophomore at my prep school when I was a senior. I don’t think I ever spoke two words to him—he called me “faggot” once in my hearing, off hand—but I lusted after him with suppressed, unspoken fervor. I gave this potent figure a new name and brought him to Mexico, setting in motion a plot based in passion and misunderstanding that could only end badly. Jack Hawkes praised the story lavishly (I was surprised!) and asked how much of it really happened (I declined to tell), only reserving judgment on my use of such gutter terms as ass, prick, and cocksucker in a work whose primary rhetorical strategies were formal and literary.

The story’s bad ending, however, dissatisfied me. Over the next year or so, when I wasn’t wrestling with drafts of Safe as Houses, I started over, discovered that the bad end was actually the climactic midpoint; that the boy who claimed to have been raped in his prep-school dorm room was a character, not a plot device; that Ethan, too, was a character and my relationship to him crucial to the ways the story could develop. “Words for Today” ultimately became a short novel of five or six times its original length called Do You Remember Tulum?

When I was first introduced as a writer she ought to cultivate to the woman who became my editor at Faber and Faber, I sent her Tulum (Safe as Houses wasn’t yet fit to be looked at). She said quite frankly that it was too short to publish. Many of the editors my newly acquired agent offered Tulum to said much the same. A number of the editors who later turned down Selected Letters wrote that, while they understood why I’d tried to make a book out of them (length), the best part of the manuscript, the part that deserved to be extracted and published on its own, was Tulum … but no bookseller would stock nor reader purchase a novel of fewer than 250 pages. First by self-publishing it nineteen years later; now with the Lethe reissue, I attempt to disprove those truisms.

The other letters are free for the taking here. I believe they’re worth preserving, the following three in their own rights as well as for archival purposes.

Letter the third

I finally moved to Boston early in 1992—that fraction of my paying work that required personal appearances was there. My apartment was not nearly so pleasant or large as Alex’s, nor was it in the gay South End around the corner from Ethan’s. Out my back window I had a view, if you want to call it that, of the nightclubs on Lansdowne Street and the horrifying green monstrousness of Fenway Park. Summer home-game nights the field lights, the growl of the PA, the roar of the crowds kept me awake. I am not a baseball fan.

At the end of August, I received notice Boston Edison would shut off power to my block over the night of 2 September. I made the bulk of my income in that era transcribing cassette tapes, recited narrative or raw interview, depending on the client—freelance work I did at home, generally at night, that depended on electricity to run tape player, computer, and lamps. Nor without power for my sturdy little Mac could I work on the novel (I believe it was Deprivation) I’d apparently assured my agent would soon be completed. I decided to take the night off and write, by hand, by candlelight, something new. A letter to Ethan, who I imagined to be out of town, visiting his family at their Jersey-shore summer rental for the last gasp of warm weather. Meanwhile, I’d stayed at home in Boston to work.

Not too long before, I’d written an as yet unpublished (best never published, doubtless) novella, an homage to the Anglo-Irish country-house novels of Elizabeth Bowen (The Last September is far better than the movie based on it) and Molly Keane/MJ Farrell, based in, if not on, childhood memories of my family’s two extended sojourns at Georgian big house Rockmount, near Kilmacthomas, County Waterford. But when I spoke to friends about that period, they were far more taken with the Jefferses’ means of getting to and back from Ireland than any stories of my residence in the Republic.

We travelled by ship. Passenger liners, in the early-mid sixties, were still a legitimate mode of trans-Atlantic transport, not yet subsumed within the Cruise Ship Experience (the appeal escapes me), but my parents preferred freighters, which might carry ten or twenty passengers along with the freight. For my first voyage, we boarded the Holland-America Line’s SS Diemerdyk in San Francisco on 15 July 1964, the day after my seventh birthday.

In “Ships at Sea” I told Ethan all about that sea voyage—inventing two thirds of it in order to give it a plot, make it a story. I’m fairly sure, though I’ve almost convinced myself otherwise, it was really my little brother who refused to wear his sailor suit to dinner at the captain’s table.

One further note. The oil portrait of my little brother and me in our sailor suits? I ended up inheriting it. It hangs in my living room, cater-corner to a sublimely lovely portrait of my mother by the same painter, while my father, in a dramatic portrait by another hand, glowers across the room.

Letter the fourth

“Dramma per Musica; or, The Frenzy of Alexander”

The lovely and talented Michael Thomas Ford asked me to write something for the porn compilation he’d sold to Cleis Press, first in the annual Best Gay Erotica series since taken over by Richard Labonté. This would have been in 1995, after publication of Safe as Houses gained me some small notoriety in metro-Boston’s gay-lit circles. I said Of course! (with exclamation point), but I didn’t quite know what.

Maybe I might come up with something reflecting my sudden passion for Italian Baroque opera seria (a passion set alight, I am not too proud to admit, by Gérard Courbiau’s riotous, ridiculous, psychologically improbable, historically inaccurate, sublimely gorgeous 1994 film Farinelli)—something that would permit me legitimately to claim all those CDs as business expenses on my tax return. Of course whatever it was would have to be set in the most serene republic of Venice, that long-standing center of my geography of the world.…

So I set to research (may I just note how much I appreciated the Boston Public Library back in the day before I had internet access?) and set to work.

Scarcely had I started Zanni’s story, though, than I stumbled across the first page or two of a letter to Ethan begun and abandoned more than two years before, on 13 March 1993, the day I appear to have completed a convincing draft of snowbound Deprivation and a day when Ethan and I were trapped in our separate apartments by the biggest snowstorm this transplanted Californian had yet experienced. In an instant of insane bravado, I resolved to mash the two together.

“Dramma per Musica; or, The Frenzy of Alexander” ended up far too long for Best Gay Erotica 1996—it would have taken up half that relatively slender volume. Clever Mike Ford chose several excerpts, however, and published them as “The Voice of the Capon.”

Letter the fifth

“Dramma per Musica” took perhaps four months to write. Several times I nearly abandoned it. The actually, truthfully autobiographical parts caused me desperate pain. Yet partway through I realized, if “Dramma” came out as long as it was threatening to, I’d have plenty enough pages among the collected letters to call them a book. But if there were any excuse for a book, it was Alex’s eight-plus-year love affair with Ethan, which was never the direct narrative focus—couldn’t be: you don’t write letters to your innamorato about your shared experiences. So at some difficult point in “Dramma,” I set it aside for a bit and commenced a letter to my friend Ilene in Germany, which I predated to the fall of 1993, half a year after “Dramma,” a letter about Ethan, about our relationship, which was going through a rocky stretch.

I took a break then, too, from opera seria. In 1994, British band Kitchens of Distinction had released what turned out to be their final record, Cowboys and Aliens. In support, they mounted a US tour, played Boston’s Club Paradise. I disliked their name but loved the band and the music. Despite my horror of clubs and rock shows (I’m prone to panic attacks in crowds), I went. It was glorious.

“Drive That Fast” is a track from KoD’s 1990 second record, Strange Free World. It might have been the first song of theirs I heard, on Providence’s modern rock radio station, WBRU-FM. Borrowing the title gave me permission, in my own “Drive That Fast,” to address acquaintances’ immediate assumption that I didn’t drive because I hated to drive, to wallow in nostalgia for the Triumph TR3A of my reckless youth, and to elaborate my fantasy of owning a Mazda Miata. (A fantasy, it must be said, since superceded by an insane longing for a series 4 Alfa Romeo Spider. I wouldn’t turn down a first or second generation Miata, though. Anybody offering?)

As well as, you know, to imagine a plausibly dull, domestic, delightful future for Ethan and me.

Postscript

The two cats who make frequent appearances in Ethan’s book, Enkidu and Element, are no longer with me. Enkidu died of old age at nineteen in 1998, in Boston, Element at seventeen, in 2000, the spring after we moved to Phoenix. The two cats who live with me now are Miss Jane Austen and Miss Charlotte Brontë, both born in Phoenix the summer of 2001.

After many years in the trunk, the novel Deprivation, mentioned several times above, reached the semifinals of the 2009 Amazon Breakthrough Novel Award. Although it got no further, the manuscript was reviewed by somebody anonymous at Publishers Weekly:

We are locked inside the mind of our protagonist for a series of long, brilliant meditative passages in this Proustian torrent. The first 40 pages of the novel begin at snow-melt pace as the reader follows Ben from a strange nightclub through a dreamy cityscape to the hideaway of two teenage boys, Dario Laud and little Gioia. This is Boston and evidence gradually reveals the time is winter, 1991. But first we swim through scenes awash in water imagery with Ben and his beloved Dario until Ben leaves for work. He is knocked down by Neddy, a cycle messenger who insists on making restitution. Ben visits Neddy and is enchanted. The following days deliver a stream of changes to Ben’s life as Paul, a teacher he’d once admired, contacts him and he meets Kenneth, who is straight but interested. The appearance of Ben’s mother Sandra’s latest novel releases even more change, leading to a conversation about psychosis and sleep deprivation with his father, Ian. “Can you date the age of reason?” Ian counters as Ben’s memories and experiences cascade with the brilliance of fountain meeting light in this exquisitely written novel.

At this writing (July 2011), my current agent is just puzzling out which presses might be sympathetic to Deprivation. Waiting. Waiting. Story of the writer’s life.