Novel.

“esto de jugar a la vida, es algo, que a veces duele”

this playing at life, it’s a thing that sometimes aches

—Enrique Ballesté

You live with someone for how many years—you make a life with him, a home, with his son too and your own nephew: it happens. They don’t tell you the stories you wish to hear, nor the stories they wish to tell, but it all works out. By now, likely as not, he’ll know more about my childhood and my parents than I do.

When Allen Pasztory discovered he was likely to die before his time, he realized that what he could pass down to the people he loved was stories. Stories of and for his families—the family he was born to and the family he stumbled upon and fiercely embraced.

The hearing child of parents raised in the inhumane surroundings of a state school for the deaf, all along Allen knew he and his family were different. His sister tried her best to become ordinary, as if it were possible, but Allen knew better. He would be ready to offer sanctuary when an ordinary family cast out his nephew Kit.

Allen fell for freelance artist Jeremy’s talent and looks, but it was Jeremy’s unanticipated bravery that supported them through the years while they nurtured their new family. Despite hostility from without and threat from within, they created a secure and loving home for Jeremy’s precocious son Toby and, later, Allen’s nephew.

But safety can’t be guaranteed. Ill, Allen must tell himself stories to survive, stories that may explain his life to the boys he’s raised, for “your life is never only your own story, and what you don’t know for sure you must invent, using all the clues you can gather.”

Safe as Houses is a gay novel about family values, the story of two men, married to each other, who raise two boys with tenderness and good sense despite a constant battle against illness and prejudice. Alex Jeffers…has written a novel as complex as humanity about how to wrest decency and love out of uncertainty. It is a book about how real families improvise their way toward love.

—Edmund White

While other novels are content to show us the surface of gay lives, Safe as Houses brings us inside in ways that enlighten and illuminate.

—Michael Bronski

Safe as Houses is…about living, finding ways to define one’s life and one’s loves, about breaking rules to create new ones, about defining the words house and home.… What [the] characters come to represent is the realization that growing and changing must include—but not be consumed by—aging and dying.

—Ed Osowski, Lambda Book Report

First novelist Jeffers controls his language to such a degree that background details—flowers, tastes, and scents—accent every scene of this domestic drama. This is a Bildungsroman with a terrible twist: the narrator is dying of AIDS.… Allen’s and Jeremy’s devotion to each other is the linchpin of this tangled world; by the middle of the story, the bleak landscape of AIDS surrounds them and then envelops Allen, whose own illness progresses until he nears the end. …Jeffers is first-rate in his ability to portray nurturing growth amid looming tragedy and to engage the reader’s interest in each character.

—Library Journal

Time and again in this wonderful, sad novel, Jeffers will effortlessly take the reader past the flat surfaces of things, into the past contained in every kind of present.

—Steve Donoghue, Steve Reads

Some books slap you in the face with action and plot in the first few pages. Others have you turning your head every which way trying to keep track of everybody. Still others slide up next to you, put an arm around your shoulder, smile and say “let me tell you a story.” Alex Jeffers’ Safe As Houses is the latter kind.

—Jerry Wheeler, Out In Print Queer Book Review

This is a story of family and love – the consuming love that grows from a family on the outskirts struggling with a vital disability – told from two different family’s viewpoints, Allen’s parents and Allen’s new family. It is a tapestry woven in vibrant detail with beautiful language.

—Alan Chin, Examiner.com

The book that had the most profound impact on me in 2010 is Safe As Houses by Alex Jeffers (Lethe Press) the story of Allen Pasztory who is ill and likely dying and who sets out to write the stories of his family as a testament of love to his lover and partner Jeremy, their sons Toby and Kit and his parents. The sheer beauty of Mr. Jeffer’s writing and the emotional integrity with which the story is written made the reading of this novel an intimate and deeply moving experience for me so much so that I’ve had a difficult time in letting go of both the story and its characters. I have re-read this novel, in whole or in part, too many times to count over the course of 2010.

—Indigene, Indie Reviews

I walked into my first ever creative-writing workshop in September 1987 and after all the introductions had been made our leader, the remarkable Meredith Steinbach (whose too few books you should track down immediately) said, Right, I want you each to write three individual, discrete paragraphs with no deliberate narrative connections among them, all from the point of view of the same character, and inspired by and/or containing these three words. (I don’t remember what the words were.) So that evening I went home and did what she’d asked. The character who spoke to me was a father talking about his young son.

The next meeting, we read our paragraphs aloud and made some off-the-cuff critiques; then Meredith gave us another three words and told us to do the same again—same viewpoint character, still no narrative. The following week, three new words, but this time we were to inhabit a different character, looking at the original. Allen Pasztory started telling me about his long relationship with Jeremy Kent and Jeremy’s son Toby.

As I recall, the exercise kind of petered out around then as we settled in to workshopping more complete fictions (in my case, several chapters of an unfinished novel I no longer care to remember much about). But Allen and Jeremy and Toby stayed in my head, growing more complicated and real. In the spring, when I worked with the late John Hawkes, they stayed in the background while I wrote the first version of Do You Remember Tulum? but that summer I pulled out those nine (or possibly twelve…maybe even fifteen) isolated paragraphs and started moving them around like jigsaw puzzle pieces, trying to find a pattern.

It took four or five years, seven or eight drafts, to discover an organizing pattern that the work’s long-time title should have suggested right away. In the meanwhile, I’d made the acquaintance of my kindly (but very stern) editor at Faber and Faber, Betsy Uhrig, who waited patiently for me to make something remotely publishable out of a huge mangy bag of pages. Finally offered a contract and oversaw the last shaping and polishing. And published the damned thing in the spring of 1995.

Not many people bought Safe as Houses, sadly—I don’t know where to cast the blame because nobody, to my knowledge, ever said anything bad about it and many were extravagant in their praise. For a while I pretended to believe it was because there wasn’t a naked guy on the otherwise lovely cover.

No naked guy on the misbegotten cover of the paperback issued in 1997 by Britain’s (now defunct) Gay Men’s Press either. I’m over being polite about the, ahem, art they did use.

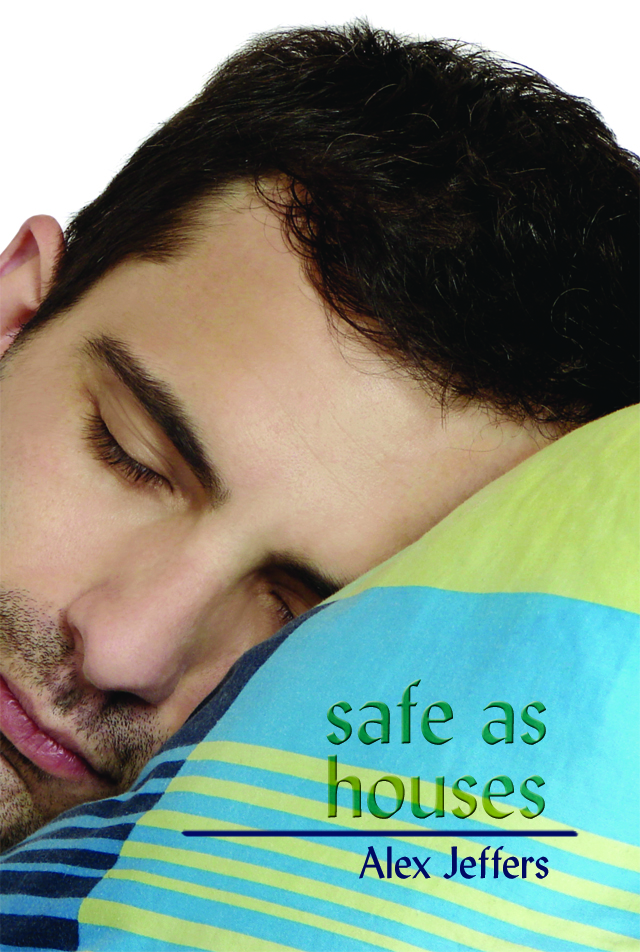

Nor is there a naked guy on the cover of the current Lethe Press edition, but don’t let that stop you from purchasing it. It’s pretty. (I designed it myself!) The not-naked guy on the handsome wraparound cover is pretty. The text itself will probably make you cry at least once.

Frequently Asked Questions

Well, not so frequently, but most of them at least once.

Safe as Houses is one of those autobiographical first novels, right? And having already used up everything interesting in your life, you haven’t been able to finish another?

::peers around (rented) apartment for evidence of husband or sons:: Umm, short answer: No. And no.

Long answer: For one thing, it wasn’t my first novel. First novel, sold to Ace Books in the early eighties but never published, thank merciful and compassionate God, was a science-fiction epic that also wasn’t autobiographical (see The New People for more background). And I had completed Do You Remember Tulum? (which I consider a novel, and autobiographical only in a very perverse sense) well before making any sense of Safe as Houses and offered it to Faber first, but they felt it was too short to publish on its own.

It’s true, however, that there’s a certain amount of autobiographical furniture lying around in Safe as Houses. Jeremy’s car, the thirty-year-old rag-top Triumph roadster, is a memory of my first car, a scarlet TR3-A, vintage 1960, and while Allen’s Volvo isn’t one of mine, I have owned two Saabs (European cars only in my household: the other two were a Renault and a VW; presently, carless half by choice, I lust for a late-eighties or early-nineties Alfa Romeo Spider). I lived for two years in the wedding-cake-pink Victorian on Sutter Street in San Francisco, although I cleaned it up a lot for the novel; and for almost four in the Fox Point Federal Revival, first in the second-floor apartment, then the attic garret.

In the late seventies, I applied to art school to study illustration. Didn’t get in, have little formal training, but still dabble—for a year or two, just recently, I was the de facto graphic designer at the nonprofit where I worked; while book design (inside and out) has recently become a consuming sideline.

But the truth is, while I find bits and pieces of my surroundings interesting enough to riff on, I’ve yet to live through a story worth writing down. Too, I have nasty scruples about putting real people on paper because, well, who gave me that right? Anyway, isn’t the definition of fiction something that’s made up?

As for the second part of the question, I completed a reasonable draft of Deprivation, a novel nearly the size of this one (the long-trunked manuscript of which landed not so long ago on my current agent’s desk and maybe now something will happen), between antepenultimate and penultimate drafts of Safe as Houses; soon thereafter wrote the rest of the pieces that, added to Do You Remember Tulum?, made up the quasi-novel Selected Letters; and by early 1999 had completed The Abode of Bliss (see also 2002, 1999, 1998, and 1996 in stories), which is novel length if not precisely a novel. Whereupon the Block That Ate New England started snacking on my head and I’ve barely shaken it off now. Although, as of December 2010, I anticipate publication of The New People—written in 2008-09, somewhat shorter than Do You Remember Tulum?—and am about two thirds through a first draft of The Unexpected Thing, which promises to be even longer than Safe as Houses. (I expect to cut it down a lot.) With the perverse exception of Selected Letters, none is any more autobiographical than Safe as Houses.

You got the title from that Depeche Mode song, didn’t you? What does safe as houses mean, anyway?

I love that song! (“Never Let Me Down Again” from Music for the Masses, 1987.) But no. I got the phrase from the same place Martin L Gore did: everyday British idiom. I spent a big chunk of my childhood in the British Isles—County Waterford, Ireland, to be precise—and a bigger chunk reading British children’s books. (Except when American copyeditors are peering over my shoulder, I still tend to spell half in British, and have a very hard time calling trousers pants. Pants are what you wear under your trousers.) I suppose it’s not an appropriate title for an American novel whose American narrator makes hay of the fact that he’s never left the country, but it attached itself to the novel in very early days and wouldn’t let go. I can only assume Allen and Jeremy read a lot of British children’s books too. The phrase means, well, very safe. Cozy and warm. Like hot cocoa on a winter night.

How about that cover Gay Men’s Press slapped on your paperback?

You know, don’t even start.

Love the photo and design of Faber’s hardcover dustjacket. Although Adrian Morgan originally planned to make the spot-color title ribbon pink! I raised a fuss and tendered the Pantone number of my favorite color. Sadly, the fuss I tried to raise with GMP over their ludicrous and sad little painting had no effect whatsobloodyever.

But how about the cover of the new edition, hey? I wasn’t thinking of Safe as Houses when I first encountered M.L.’s photo and saved it to my iStockphoto lightbox—I don’t quite recall which project I was browsing for. My notions for the cover of this reissue all involved houses but I was thinking too literally. The second time I saw the handsome young man asleep, safe as houses, the deep intention behind my choice of the title asserted itself, and there you go.

Speaking of the reissue, if I already own a copy of the Faber or GMP editions do I need to buy the pretty new one?

I’m sorry, need? Fiction is a luxury good—you never need to buy a novel.

That aside, still probably no. The text scarcely differs: I changed, I think, three words (one of which appeared twice) and fixed two typos—neither of which, may I point out, got past me at Faber’s proof stage but which were nevertheless not corrected (all the others I caught were). It even retains American spellings the original copyeditor insisted on but I don’t favor. At the same time, for one reason or another, instead of using an old electronic file to set this version up I retyped it beginning to end so it’s entirely likely new errors have crept in despite rigorous proof reading.

Interior layout and design are quite different (GMP used Faber’s plates to print the paperback so there’s nothing to choose between them) because I wanted to try a couple of things. I don’t know that that’s a good reason to stuff another version into your bookshelves. As you have already seen, the cover is new—neither better nor worse, to my mind, than Faber’s, but different. If you own the GMP paperback and the cover doesn’t cause you to wince every time you pull it out for a reread, by all means stick with it.

Why did you decide to make Allen’s parents deaf and how did you learn about deaf culture?

“From The Bridge” (see stories, 1992), written in the early eighties, was intended as the first in a sequence of science-fiction stories about a balkanized, alien-occupied future San Francisco. At the time, I worked in a public library and saw a lot of new books, took home any that looked interesting. One was a history of the manual/oral controversy in deaf education. Fascinating. I drafted a story about an enclave of deaf gay men in my future San Francisco, but it never satisfied me. Still, when I saw them, I kept picking up and reading books on deaf culture because you never know. But let me just say here that I didn’t study sign nor sought out deaf people for firsthand research, then or later. That’s not how I work (social anxiety? old friend of mine).

Fast-forward to Providence, 1987. I’m developing this character, this guy Allen. Looking back at the last substantial thing I wrote, I’m appalled by how the protagonist lights a cigarette every other fucking page. So I’m resolved Allen won’t smoke. (Wasn’t entirely successful in keeping that resolution, now, was I?)

But what’s he going to do with his hands?

Why are they Hungarian?

Allen needed a surname. I liked the sound of Pasztory. (Peace story. Also, shepherd.)

You know, Toby is too good to be true. I have some issues with believability around Jeremy and Kit, too.

Ever hear of an unreliable narrator? Consider Allen’s position, consider why he’s writing these damn documents. You think he’s not going to do a little sugar frosting?

It’s a gay novel, right? Why isn’t there any explicit sex?

Pp 340-41 in the Faber and GMP editions, 383-85 in the briefly available self-published edition, 274-275 in the Lethe Press edition. Amuses me no end that everybody seems to skip right over that. Once made some straight friends of friends very uneasy by reading that passage aloud at a dinner party.…

I saw you at one of your readings when Safe as Houses was first published. You were scary thin and looked kind of shaky. Are you HIV-positive?

Thankfully, no. I did have a scare my first summer in New England, ie, in early days of the first draft. I kept waking up in the morning to find myself and the bed soaked. Night sweats—that’s a symptom, isn’t it? Oh, god, I let that guy fuck me without a condom four years ago! Doomed!

I hadn’t lived in a place with hot summer nights in a very long while. You don’t sweat at night in coastal Northern California.

As for the shakiness, I mentioned something about social anxiety, didn’t I? (I’m still scary thin, too.)

But it must be said that Allen was already sick before that scare. It was the second or third thing I knew about him. I don’t know about other writers, but to me, rightly or wrongly, in the late eighties, it didn’t seem possible to write about gay men without centering the epidemic. At the same time, however, I didn’t wish it to be an AIDS novel, or not entirely, which is one reason I borrowed Robert Ferro’s technique from Second Son of never naming the illness.

Who’s Robert Ferro?

I despair of gay culture’s short memory and publishers who won’t keep good books in print. Robert Ferro was, with Edmund White, Andrew Holleran, Felice Picano, a member of the Violet Quill writing club in New York in the seventies. You’ve heard of them and it, right? He published four novels, The Others, The Family of Max Desir, The Blue Star, and Second Son. Max Desir made him as famous as he ever got; deliriously romantic Blue Star is my favorite; Second Son, to my mind the only “AIDS novel” that succeeds as both a novel and a document of the epidemic, besides ripping me to shreds every time I reread it, was written while he was ill and his husband dying. They’re out of print but you can find used copies. Do so. Now.

I assume [correctly—AJ] that the university mentioned now and then in the Providence chapters is Brown. Is Allen’s school also real?

Its location and some exterior details are stolen from the Moses Brown School, a deservedly well respected Quaker institution, founded by a member of the family the university’s named after. Everything else is made up, doubtless with some unconscious input from memories of my own prep school in California. Same goes for the school Allen attended in New Hampshire.

Why are Allen and Jeremy such guppies?

Does anyone still use that term? Gay Urban Professionals, for those who missed the memo.

And are they, really? Jeremy works part-time, freelance, from home. Allen falls into his two careers by accident (and, you know, I don’t think he was ever very good at advertising). But what you’re really asking, right, is why they have a nice income and a pleasant, superficial, middle-class lifestyle, instead of a gritty, authentic life full of drama and violence, I don’t know, on the mean city streets, as prostitutes and addicts. Yes?

Well, look. I live a pretty marginal life myself (at this writing my latest stretch of unemployment has run six-plus months)—not on the streets maybe, but soon after Safe as Houses was published I was on the point of being evicted until a friend lent me three months’ back rent. The only house I’ve ever owned would have been foreclosed if I hadn’t declared bankruptcy; lost it, in any case. I don’t have a career, professional or otherwise, or a retirement plan—the vast majority of my jobs, the last twenty years, have been through temporary agencies, at not much better than minimum wage. I may not have turned tricks (god, that would involve interacting with strangers!) or been addicted to anything but tobacco, but as far as poverty cred goes? I’ve got a certain amount of it.

And you know what? In my experience, poverty sucks. It’s aggravating and annoying and scary and dull and deeply, deeply, thoroughly and entirely tiresome. It’s not exciting; it’s not romantic or colorful; it precludes a tremendous number of possibilities. It takes up all your time. And I don’t wanna write about it. My privilege.

Will you ever write a sequel?

I already did! Well, not really. There was a chapter I had trouble finishing that I intended to place between “Wind on the Water” and “Awaken,” in which Kit and Toby start a gay-straight alliance at the school and Allen mentors a scared gay teacher. After the book went to press, I did manage to complete it but it wouldn’t have fit anyway, too political and angry. If Faber had taken the short-story collection my editor asked for after Safe as Houses, it would have been in there. But here “Avuncular” is now on the internets. Belated epilogue or postscript more than sequel, I suppose.

But a formal, full-length, novel-type sequel? Unlikely. Oh, sure, Allen (and Jeremy) could well have survived into the era of protease inhibitors and multi-drug-cocktail maintenance. Make it through to ’04 and they could relocate to Massachusetts and get married for real. (I got a whisper away from it myself, in ’05.) Toby can bring grandchildren to visit … Kit too. I’ll let them do that in your head.

Any other questions?