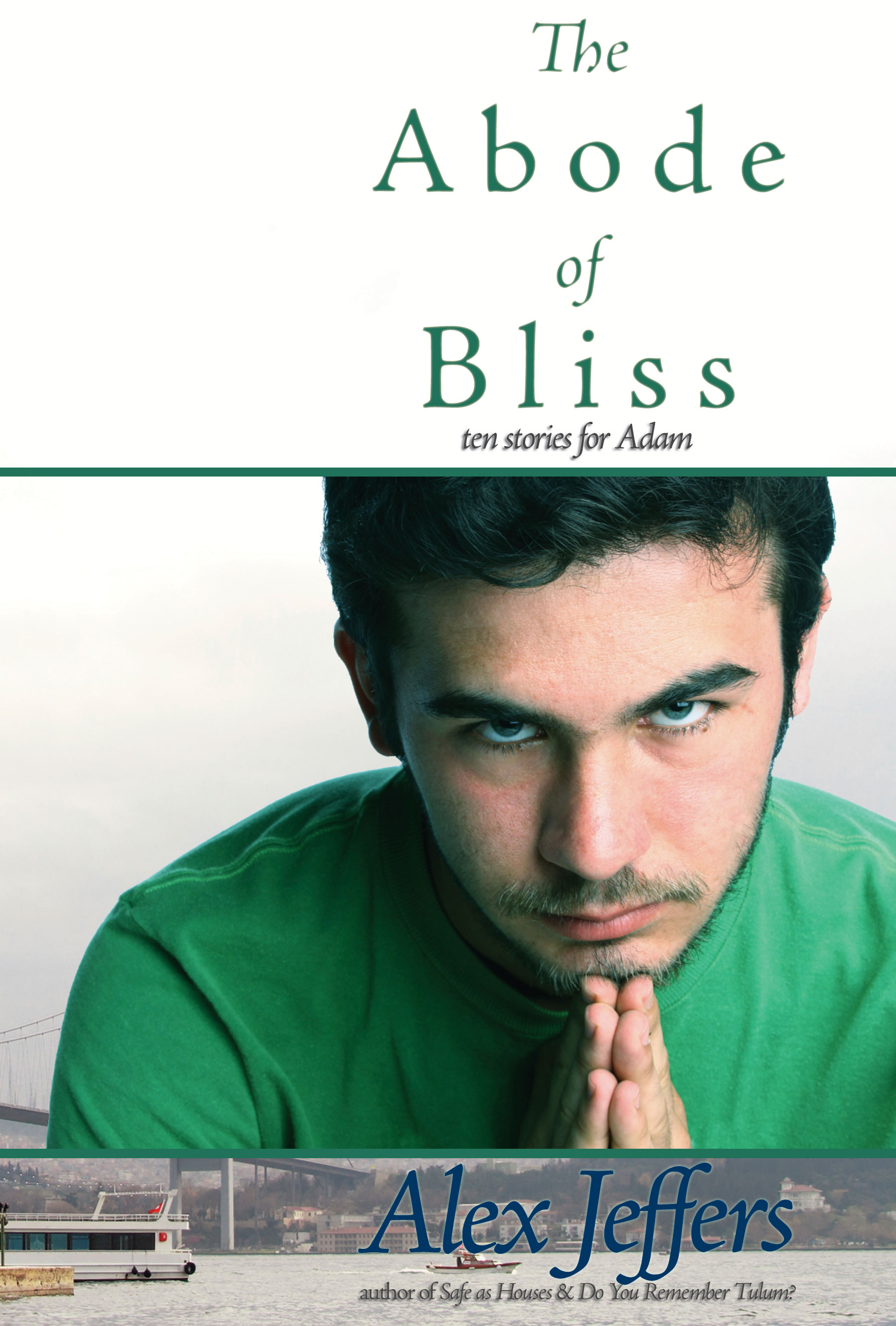

Now available from Lethe Press, a bildungsroman of linked stories.

“The nation of love differs from all others

Lovers bear allegiance to no nation or sect”

—Mevlana Celaleddin Rumi

We had a house in Bodrum, he said to his friend, without the traditional storyteller’s preface, bir var miş, once there was, bir yok miş, once there wasn’t, maybe it happened and maybe it didn’t, and we went there for a month every summer. My father had investments in Bodrum—he felt sure the town had potential to become a major international resort. He was right, of course, my father, and we are very nearly rich because he was right. But this was years before.

Explaining himself to himself and to the man he loves, Ziya tells Adam the stories of his life:

A bilingual childhood and youth in cosmopolitan İstanbul, city of the world’s desire, and the Aegean resort of Bodrum. A bewildering trip by ship and train and jet across Europe and the Atlantic to college in America, that strange and terrifying country. Friendships, passionate affairs, one-night stands, rape—a richly dissatisfying erotic education. A wedding, a death, an act of inexplicable violence—a meeting.

Intricate as Ottoman miniatures, Ziya’s stories reveal a world unsuspected: the world we live in.

Waiting fifteen years to read something new from Alex Jeffers was well worth it. This collection is a treasure chest of perfectly-polished gems, each one radiating an inner beauty brought out by evocative prose, rich characterizations, and a strong sense of place. A rare treat indeed, it is over all too soon and leaves you longing for more.

—Michael Thomas Ford, author of What We Remember

Here is a book of stories in which each one is sheer perfection. The prose is sublime, the characters are beautifully drawn and we get a chance to see what the word literature means (as opposed to writing).

—Amos Lassen, Reviews by Amos Lassen

The Abode of Bliss is written like poetry, a trip for the senses for one to enjoy from a distance.

—Katie Drexel, Edge Media

I’ve long believed that Alex Jeffers is a remarkable talent. I regard The Abode of Bliss as his most impressive work to date. This is a book I will read, savor, again and again. I highly recommend this book to everyone who loves finely crafted prose, lush descriptions and gratifyingly deep characters.

—Alan Chin, A Passage to Now

…what of my high expectations? I am happy to say that those were met, and then some. This is a fabulous work of fiction by Alex Jeffers and one I highly recommend.

—Hilcia, Impressions…of a Reader

The book asks questions about national identity, about what it means to accept religion and at the same time not to be a very religious man. It asks so many subtle questions that after two rereads I am still pretty sure I missed some of them.

—Sirius, Reviews by Jessewave

I find myself wanting to share so much more of this sublimely eloquent work. I’ve probably shared too much. I want, I suppose, for you, the reader to love this book as much as I did; the storytelling is as engaging as anything I’ve read in a very, very long time. And, too, I hope you (like me) will find the introspection urged by Ziya’s storytelling not so much as an explication of the ugly American, but rather a worthy reflection on who and what we, Americans, have become.

—George Seaton, Out in Print Queer Book Review

A 2012 Over the Rainbow Book selected by the GLBT Round Table of the American Library Association.

The book was an incredibly personal reading experience for me as it transported me back to my own childhood and memories, both good and bad, of my paternal Turkish origins. It is incredible to me that Mr. Jeffers, who is not of Turkish descent, has written a story that so intimately captures the ethos and nuances of Turkish life and culture. I believe this is an innate talent that requires an intuitive sensitivity, understanding and ability to immerse oneself in a writing subject that no amount of research can achieve. Mr. Jeffers possesses these qualities in abundance. …I cannot recommend this book enough.

—Indie Reviews: Reading Round Up: The Best in LGBTQ Literature for 2012

The Abode of Bliss by turns made me laugh and made me weep. Reading it I felt both lonely and loved, and was filled with longing, both sexual and romantic. The prose is poetic though not overblown or contrived. It is evocative and heartfelt but with an emotional distance, as if the story teller is remembering, that allows careful observation. But still I felt close enough to be pulled into the remembered emotions, to cheer and cry for Ziya. I felt entirely inside his world, inside him, a character made up only of a words on a page.

—Ajax Bell on her blog

As originally conceived, The Abode of Bliss was meant to be a proper novel with a plot and everything. The viewpoint character, Adam, a failed novelist living in genteel poverty in Boston, scraping by transcribing novels and memoirs for writers who refused to type (ha! story of my life in the early ’90s, and I claim not to write autobiographically), would fall in love with a Harvard student, a foreigner. The lover, after graduation, would outstay his student visa and be deported: the trauma at the center of the novel from which would spin out the plot.

My inspiration was an article in Out magazine, 1994 or thereabouts, profiles of gay and lesbian illegals attempting to claim asylum in the US because of the persecution they would suffer living openly at home. One of the subjects—there were photographs—was an intoxicatingly lovely young Turk named Serkan Altan.

Serkan would later become the first gay man to be granted asylum without having to sue; would be photographed nude for Freshmen magazine and voted Freshman of the Year; would make something of a name for himself as a go-go boy in Washington DC; would write a memoir that (we shared a literary agent at the time) I would badly fail at rewriting for him. We had several pleasant phone conversations, and I felt horrible when I finally admitted I could do nothing with his book (never published, to my knowledge), and now feel mildly horrible that I don’t know what’s happened to him since.

But long before any of that, I had taken the coincidence of Serkan’s beauty, a recent reading of Mary Lee Settle’s Turkish Reflections: A Biography of a Place, my elder brother’s recollections, from student hitchhiking days, of the Turks as the friendliest people in the world, and my own conviction that, if God were merciful and compassionate, he would have arranged for me to be born in İstanbul, to mean Adam’s beloved must be a Turk.

His name was Ziya, which sounds to Western ears a woman’s name, but it was Turkish, a simple word, a noun that meant (he told Adam later, later, ashamed or shy because in America names didn’t mean, were illegible sherds of an antique past so that you had to look them up in dictionaries of dead languages, and a man’s name, when you puzzled it out, was either forthright or banal—in Turkish, fortuitously, adam meant man, person, individual, but it was not a name—and a man’s name didn’t end in -a): it meant light. Light. Illumination: Adam thought: luminance, luminosity—luminous Circassian blue eyes, pale as glass: as luminous and glittering beneath black brows as the windows of a darkened house where the television is on. A not-uncommon name, in Turkey, for a favored son, and how it must have been at evening in Emirgan or Bodrum when his mother stood at the door and called out: Light! O, Light! Come in now! The power had failed for the second time that week and the Ottoman sickle moon hung in the sky with a star between its horns, and the echo of the müezzin’s cry seemed still to hang like a translucent, fading silk pennant of sound, settling over the town, and the boys were playing soccer in the twilit streets—O! Light! Come home!

There were several problems with that vision of The Abode of Bliss. Adam and his unremitting melancholia bored me very quickly. His soap-operatic family made me laugh and cringe. The tortuous over-the-top-lyrical prose he demanded was a strain to keep going. The subplot involving the ghost of an early-twentieth-century American diplomat was unwieldy and probably out of place. After Safe as Houses, Do You Remember Tulum?, and many other works, finished and unfinished, published or not, I was weary unto distraction of American gay men, my peers, and their first-world problems.

Chiefly, Adam (and I) had fallen for Ziya because he was Other: I had, with all good intentions, walked right into the Orientalist trap.

The beloved is always Other, Unknowable, to an extent, or one would cease being fascinated, so it wasn’t Adam’s problem so much as mine. He could fall in love with a stereotype; I couldn’t in good conscience knowingly write one. I needed to know Ziya as well (or better) as I did Adam, inside and out.

So I began to research and Ziya began to tell Adam stories of his life before their meeting. For a year or two I intended to splice Ziya’s stories into Adam’s narrative, interludes. Ever increasing word count killed that plan. Then I resolved to write three books. First would come Ziya’s memoirs; second, a volume of fictions composed alternately, then collaboratively, by Adam and Ziya; third, the original novel.

That remained the plan up until I completed Ziya’s tenth story, in which he met Adam—his life intersected with Adam’s plot—at which point I realized I had written another novel-length NOT A NOVEL, as unlikely to be understood or appreciated by commercial publishers as Selected Letters, the odd conglomeration that tried to make a book-length book of Do You Remember Tulum? My agent, bless him, made sure I understood he couldn’t understand how I expected him to market it, despite the many felicities and beauties he was happy to acknowledge.

Thereupon, I fell into a peculiarly manic depression (among other insanities, I fled Boston for nearly five years exile in the desert Southwest) and a writer’s block of nearly ten years’ duration.

Through it all, I remained convinced The Abode of Bliss was both a legitimate book and contained some of the best writing I would ever be capable of. Attempts to transform it into a conventional novel were doomed to failure: it was what it was. And finally, in my friend Steve Berman of Lethe Press, the book has found a publisher willing, quixotically, to take it on its own terms and take a chance.

The book of Adam’s and Ziya’s fictions is unlikely ever to be written. Adam’s novel as originally conceived is almost sure not to be. But now that I’m writing again, I have a notion for a more symmetrical companion volume: ten stories for Ziya. That book, The Gate of Felicity (or possibly The Nation of Love), will have to wait for other projects, however, so don’t hold your breath.