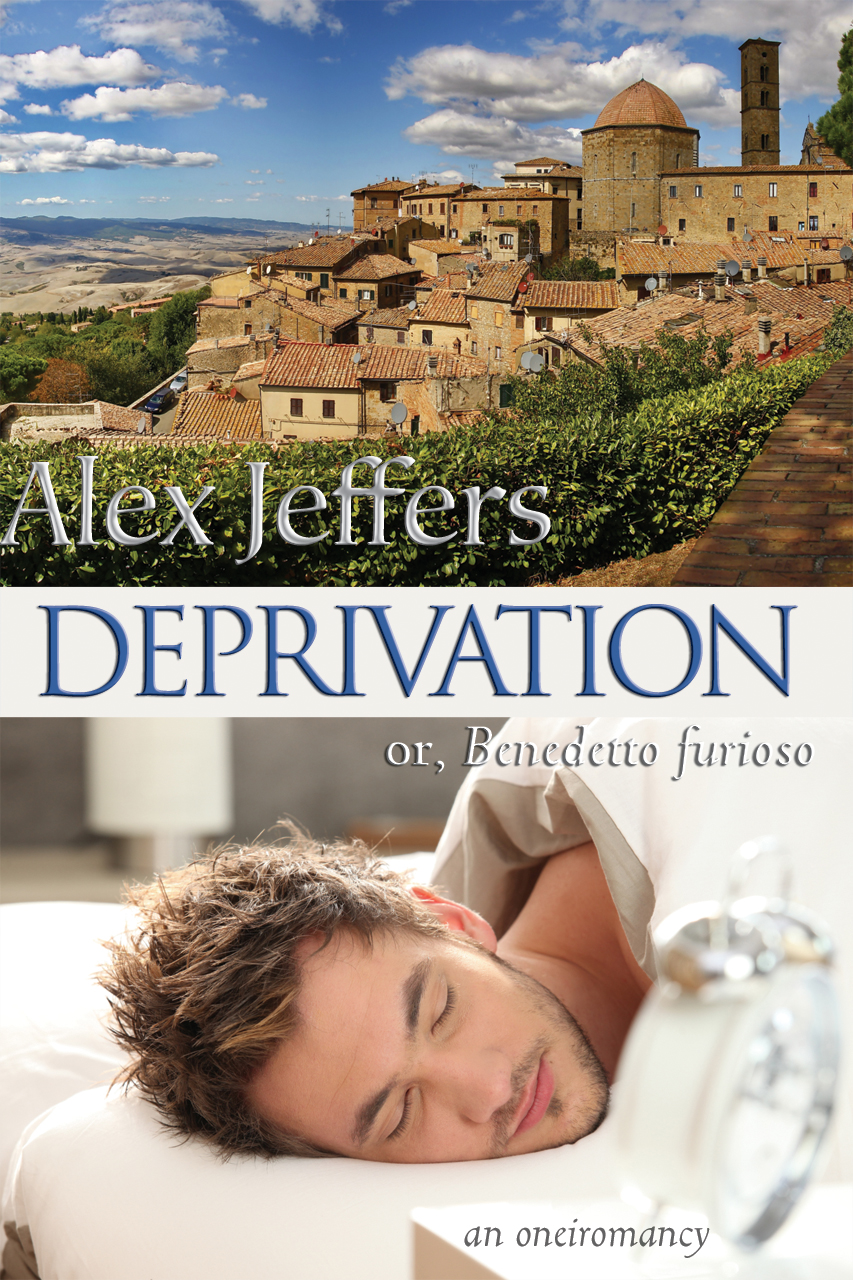

My second full-length novel and sixth book, Deprivation; or, Benedetto furioso: an oneiromancy, has gone to press. The print edition should therefore be available (through Amazon at least) by the official publication date of 28 February. Currently preparing conversion files for Lethe Press’s e-book wizard, in expectation of electronic versions for computers, tablets, e-readers, and—who knows how people read novels these days?—smartphones going on sale right around the same date.

So how about an excerpt to whet your appetite?

This bit comes late(ish) in the book but, in its way, I think, epitomizes many of the themes and approaches I was aiming to hit.

In the dream, Ben was walking with a friend. More peculiar than the fact that he couldn’t get a grip on his companion’s identity (his features, if Ben glanced to the side, were lost in a sunny glare, his voice was, in the dream, characterless, his speech had the uncanny quality of being transformed, in Ben’s hearing, instantly from phrase to paraphrase)—even more peculiar was Ben’s certain knowledge of where they were: they were in Italy. Not really, of course (it was a dream), for how could you dream of a place you’d never been? A pastiche Italy cobbled together from his reading—as much Browning or Forster (or Alexandra Benedict) as any native writer, from films and paintings and those volumes of shockingly beautiful landscape photographs he bought off remainder tables, from history, cartography, memoir, occasional essay—all the drugs of the armchair traveller, from imagination, too, and longing. A counterfeit Italy, then, to which you couldn’t attach names from any atlas—and only a province, truly, of the vast Italy of dreams, a tiny territory you could cover on foot in a morning.

They were walking. The narrow lane wound among the foothills of a massy range of which you caught glimpses from time to time, shouldering up into a sky that was, overhead, cloudless and a dry, powdery blue, deepening and greying through imperceptible hazes and washes into and beyond the mountains. Knuckles and fists and elbows of rock, tawny or purple or grey, protruded here and there from the green flesh of the range. Crowning one sheer scarp, a mediaeval fortress raised a beetling round keep and square watchtower built of the same stone so it appeared to be carved from the crag itself. But you’re walking among sloping meadows, through groves leafing out in the spring warmth, in shady, bosky valleys beside clattering small streams. From the mosses at the roots of trees you pluck odorous violets or buttery aconites for your companion. A clearing ripples with waves of creamy narcissi, and anemones with petals like the veined, gauzy wings of insects.

The lane climbs slowly, taking into account dips and swales, but with certain purpose. Angling across a shallow slope washed in sunlight, the roadbed is dusty and flinty, but below you a succulent pasture spreads velvety green skirts embroidered with tiny flowers over the folds of the hillside. On the far side of the broad valley a steeper incline, its verdure blued by the distance, is spattered with small white blots: sheep. In the valley itself, lines of slender trees—cypress, poplar, beech—mark other lanes and roads and the boundaries of cultivated fields. A slow civil river flows through it. Made toylike by distance, the pediment and winged façade of a Palladian villa are reflected in the river’s waters, among the trailing streamers of great willows. The villa’s many green shutters are all closed, the umber stucco patchy, the box-hedged formal gardens overgrown. A chestnut lifts white candles. The plumy silver-green torches of poplars, dark pyres of cypress.

And all the while as you walk, you’re talking, you and your companion, laughing, the easy unmemorable conversation of dear friends on a ramble. You can’t retain a word of it. Once he chases you a few hundred feet along the lane, another time you trip him into a meadow of sweet grass where both tumble end over end a short way down the hillside, breathless. Sometimes you walk hand in hand, or you drape arms over each other’s shoulders and stride lockstep, a single creature whose shadow has three legs and two heads. Or, content, you amble separated by a few feet, where the lane lies sunken a bit below the dry soil of the prosperous vineyards.

And now, over a slight grade, you find yourselves on a crest. Below, the slope falls broken through a deep ravine, and across, where it rises again, less steeply, the buildings of a village or a small town clamber along a bent spine of granite. Somewhat lower than your own position, the town flaunts its pitched, pantiled red roofs, crazily splayed out from their roof beams like the heap of opened books on an invalid scholar’s counterpane. At the tip of the ridge stands the Baroque campanile of a small church. The bells toll noon, bright and hollow across the gulf. The grey stone and ocher plaster faces of the buildings absorb light and heat, inhaling it through thick walls. The glass of many small windows glitters. Down the bluff your paired shadows rush, the negative relief of quicksilver, and one of you confirms the other’s hunger, his agreeable fatigue.

Taking hands again, encouraging each other, they took to the lane again. It headed downhill at an angle to the slope, with long grasses overhanging the path from the bank above, the roots of old olives knitting the bank together and the shadows of their leaves making patterns like dense shoals of tiny fish on the roadbed. As the grade steepened, Ben and his companion walked faster, until near the bottom of the gully they were running, gasping out the names of the dishes that might satisfy their appetites. A swift cold stream was bridged here. They paused to splash their faces, cool their wrists, rinse their mouths, and then they kissed, and then they went on again, upward now.

Even kissing the man, Ben had somehow not been able to make out his face, determine his identity. It hardly seemed to matter, though, for he knew this was (or was to be) his life’s companion, the love of his life. There was the certain familiarity in the ways their hands and lips met, the way the two sides of their conversation met without exception, requiring no explanation, as though there were no barriers. A passion lay exposed between them that need not be iterated for it was expressed in their simply walking side by side, and which, contrariwise, made walking side by side an exercise in revelation: Ben saw everything (if not the man himself) more clearly, as though he was storing up image and incident for the narration of their shared story. And there was a simple friendliness, a kind of joy both domestic or intimate and ecstatic, universal. You felt that here was life’s purpose: a small, manageable objective well within the scope of a man’s ambition.

Maybe I’ll toss up another excerpt on the day itself….