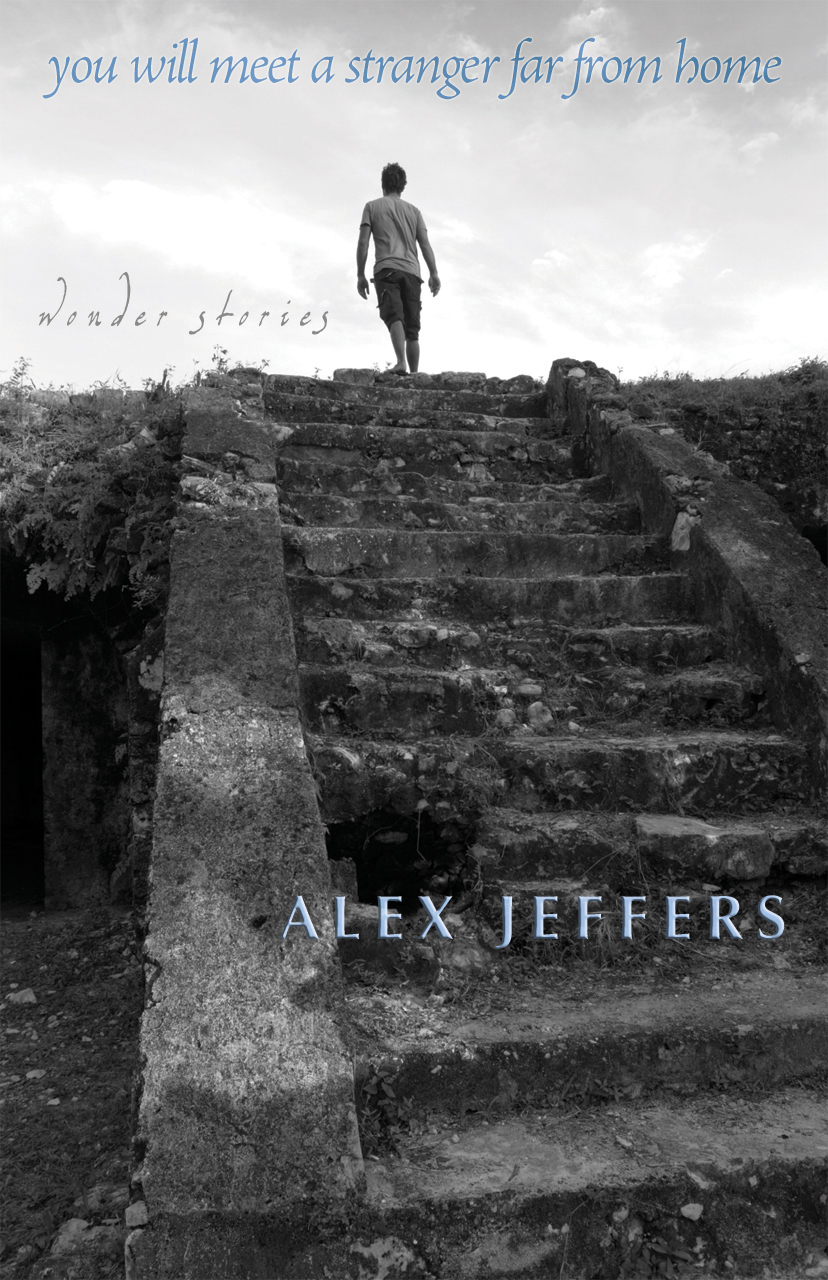

And so today, my mumblety-fifth birthday (but more worthy of commemoration as Jane and Charlotte’s eleventh), You Will Meet a Stranger Far from Home officially begins its journey into the great world. (The print edition, that is. E-books will become available in a matter of weeks, I expect.) Fare well, little book of wonder stories, fare well!

If you haven’t yet decided whether to buy a copy, how about some encouragement? Here are three favorable reviews: Publishers Weekly and Benito Corral Reviews and Out in Print.

Teasers? Two of the previously published tales are already available on line: A PDF of “Firooz and His Brother” (originally published in F&SF, May 2008) can be downloaded at my publisher’s website (“A Free Gay Story” in the navigation menu). “Tattooed Love Boys” is on line at GigaNotoSaurus (you can also download an e-pub for your e-reader), in a version that differs only slightly from the one in the collection.

Or you can stay right here and read a story originally published two years ago in Icarus. It’s on my mind because I just started constructive thinking about the fourth Liam story. Although there are so many other tasks I ought to be accomplishing instead. Dammit.

Liam and the Wild Fairy

Liam missed the school bus. Deliberately. From the far side of the rutted athletic field, he watched the yellow monster trundle away with its monstrous cargo and pulled out his phone. When he flipped it open, the animated carrousel of tiny family-n-friends photos-n-unassigned-ikons spun for a second before it settled on his dad grinning up at him. Dad #1. They’d been fighting, but still. One kept up the forms or got grounded. Liam thumbed the call key and lifted the phone to his ear.

It went to voicemail, probably not deliberate. Liam waited for the beep, then said with great fake cheer, “Hey, Dad. Missed the bus—” again would be taken as understood—“so I’m walking home. See you in forty-five or so. Love you.”

Folding the phone shut again, he stuffed it back in his pocket and started walking. It was only about a mile and a half, rural roadsides until he reached the park, and he did like to walk. More than he liked trying to ignore Harry and Brandon and Tyler and the hurtful things they said that made the girls giggle meanly and put Joel’s back up. Why the only kid in the freshman class who could make sophomore Harry back down should be bothered Liam didn’t like to think about—he disliked feeling beholden and Joel’s interference just made Harry and his pals more vindictive when he was out of sight.

There was always the worry Harry would get off at Liam’s stop—Harry lived only two lots away—and try to start something. He’d done it before. Harry was a coward and his folks were Christians of the hateful sort who’d been piously gratified when Liam’s dad #2 decided he didn’t like being married or a dad anymore and ran away to California. Except Bryan, Dad #1, didn’t then choose to remove the foul contagion of himself and his son from the Hogans’ neighborhood—Bryan and his former husband had bought their house two years before Harry’s family arrived. Would the Hogans have settled here if they’d known beforehand?

Liam’s phone vibrated against his thigh. He pulled it out again, checked the little display on the outside of the clamshell. “Hey, Dad.” Who else would it be?

“What was it this time, Liam?”

Liam shook his head. It wasn’t like he could be grounded from school. “Just ran a little late.”

“No baroque excuses to entertain your old man this time, huh? It’s not especially convenient for me to come pick you up right now.”

“Better not to spew more climate-change toxins into the air anyway.” Liam shook his head again, determined to take the high road. “It’s a nice walk. I could use the fresh air and I’ll get home long before dark.”

“You want fresh air, join the cross-country squad.”

Liam had a hard-fought exemption from PE. His dad had done most of the fighting.

“Babe—” The ritual endearment sounded inflammatory. “You know Ms Abadi reports you every time you’re not on her bus and I get a call from the principal the next day.”

“What are they worried about?”

“They watch the news. The district’s legally responsible for you till you get home.”

Liam glanced around. Every house within town limits stood on at least an acre. A certain amount of quixotic family agriculture stretched out the distances even further. Visiting friends—if you had friends—you had no choice but to hike or bike (Liam didn’t have a bike) or get your parents to drive you. “Sex criminals can’t afford to live in this town, Dad,” he said, trying to sound reasonable. “Like they’d be interested in me anyway.”

“You might be surprised,” his dad muttered, then more clearly, “I’m actually more concerned about the high-powered jerks who can afford high-powered cars, don’t believe speed limits apply to them, and get distracted when their cell signal drops.”

“You know I’m careful.”

“I know you’re careful. You’re not driving an overclocked SUV.”

“I’ve got eyes in the back of my head.” Not literally, but Liam was fully aware of the three tons of steel coming up behind him even though he couldn’t quite hear it yet. The driver was going slow, would see Liam’s fire-engine-chartreuse backpack in plenty of time. In the far lane, in any case.

“Harry and his bastardy posse again, or was it somebody trying to make friends?”

“Hey, now. They’re not bastards. Their parents were legally married when they spawned.” Liam took a breath and watched where he put his next foot. No way he was going to address the other issue right now. “Look, nothing happened. I just had kind of a long day and didn’t feel like dealing with anybody and it’s a pleasant afternoon for a walk.”

“Liam. It’s high school. Some kids are going to be mean and stupid no matter what. If you had friends—”

“I don’t want friends, Dad.”

“Everybody—”

“I’m not everybody. You know it as well as I do.”

The truck had sped up. Liam could hear the deep growl of its engine but didn’t look back as it rounded the curve behind him. On the straight, it sped up faster, staying within the speed limit and its own lane. Incurious, he glanced over as it levelled with him, in time to recognize the older brother of one of Harry Hogan’s friends at the wheel of the big black pickup. In time, if there’d been any real chance of it hitting him, to dodge the soda can that came flying out the open window. Liam didn’t break stride. “Fairy!” the kid yelled—your hearing had to be as acute as Liam’s to catch it over the engine noise. He watched the can bounce off tarmac onto the shoulder and roll into the ditch.

“What was that?” his dad asked, jumpy.

“Truck passing. Gave me plenty of room.”

“Why don’t you want friends, babe?”

Halted, Liam regarded the soda can glittering in half an inch of muddy water at the bottom of the ditch. “Dad—” He resolved to ride the bus every afternoon for the rest of the year, no matter what. His dad didn’t understand about not rocking a half-sunken boat. He didn’t want to get into it over the phone—didn’t want to get into it at all but particularly not now. Maybe he was a little jumpy himself. “We can talk about it when I get home.” Again.

“Liam—” Bryan swallowed whatever he meant to say. “We’ll do that.”

“I’ll be there soon.”

“You’d better be, son of mine.”

It would be that conversation again, the one about driving him to and from school every day if the bus and the kids on the bus were so intolerable. Wouldn’t that just improve Liam’s image among his peers. Then the subject of private school would come up. As if his grades were good enough to get him into one. As if prep-school kids were magically less small minded and hateful than other adolescents—as if Liam would magically become a different boy himself, ready and eager to join in. And then, if Liam didn’t nip it right in the bud, there’d be sad musings about sending him to live with Dad #2 and his new boyfriend because surely high-school students in San Francisco were more enlightened. “Their parents voted to repeal gay marriage,” Liam would say (had said), and Bryan would say, “Not San Francisco parents,” and Liam would have to say, “Ricky and his guy don’t want me.” Which was so true it didn’t even hurt anymore but it wasn’t supposed to be spoken aloud. Besides, the prospect of living in a city terrified him.

Liam kicked at grass sprouting at the road’s edge where asphalt crumbled into dirt. Recovering, he noticed the soda can in the ditch again. Feeling virtuous (soda cans were aluminum, safe to touch), he clambered down to pull it out. There were no sidewalk trash cans around—no sidewalks—let alone recycling bins, but he was almost to the park.

Reaching it, he detoured off his regular route to find the bin marked CANS ONLY by the little kids’ playground. When he got there, though, he discovered the battered plastic receptacle had been replaced by one of those high-tech solar-powered compressor bins. The handle you had to pull down to deposit your can had the look of brushed stainless steel. He hesitated a moment before reaching for it. The sting of incipient burn bloomed in his fingertips before they got within three inches and he snatched his hand back. “Dammit,” he said, blowing on his fingers. “Try to be a good citizen….” It wasn’t worth the effort to go digging through his backpack for gloves. Easier just to carry the grotty soda can the rest of the way and drop it in the recycling at home.

Liam started walking again, not really paying attention, holding the can away from himself in case it dripped. He hated the smell of every soda he’d ever encountered—he was pretty much allergic to high-fructose corn syrup and aspartame was worse. The dirt path away from the playground led him under tall trees alive with new leaves. He inhaled the fresh greenness gratefully. Leaves and pollen and damp earth mingled and murmured and calmed him. This was one reason not to ride the bus. The fug of growing boys and girls and their rampaging hormones, the horrible industrial fragrances they felt honor bound to steep themselves in, the horrible foods they ate and the odors the foods caused them to exude…it was difficult enough to withstand in large classrooms with climate control. Concentrated within the vibrating, painfully metallic capsule of the bus, it became unendurable. By the time he got home, always, always, he would be queasy and nearly high.

He suspected it was hormones made big, tough Joel so stupidly protective and friendly. Just today, Joel had barged up to the table in the cafeteria where Liam was eating his home-made lunch to ask about the book he was reading. Liam had to insult him hard to make him go away, and then Joel looked so sad and hurt Liam felt kind of bad. Not bad enough to go after him and apologize, until it was too late to carry through without raising Joel’s expectations. Whatever Liam’s own freaky hormones were doing to him, it didn’t involve irresistible urges to get close to people or find them sexy—whatever that meant. Joel’d been wearing a tight t-shirt, too short so that when he stretched (deliberately, Liam thought) half his taut belly came into view, navel winking: a fool’s errand if the display was meant to get a rise out of Liam.

His dad was naïve and solipsistic to believe all Liam’s problems rose from Bryan’s being gay, having been gay-married and now gay-divorced. Not that it didn’t reflect badly on Liam, but he wouldn’t be less…sensitive if he’d been adopted by a white-bread str8 couple who called him Bill. Actually, the white bread would probably have killed him long ago.

Walking along the path, thinking too freaking hard, he stripped a tender lime-green leaf off a low branch. Bruised by his fingers, it smelled so good that he raised it to his nose and crushed it and then, intoxicated, stuffed it into his mouth. The juices were clear and vivid, more alive than the brightest Florida orange or the pomegranates his dad bought him in the winter. Concentrating on the complex flavors, the textures of the leaf’s fibers mashed and wadded by his teeth, he tripped.

The soda can flew from his hand, tinkling into the underbrush. Liam yelped, more surprise than pain, when one knee and then a palm struck the ground. The lump of masticated leaf had caught in his throat, as minorly distressing as a stone in his shoe. Lying still for a moment on soil that felt chillier than it really was, he became aware of tears starting from his eyes and grunted, “Clumsy.”

“You are bleeding.”

Liam yelped again, startled. The leaf came up, sweet, unexpected, as he imagined bubblegum might taste. He spat it away.

“Please. I can smell it.”

Ready to flee, Liam rolled up to a crouch. The voice didn’t sound human, clear and thin and edgy, like struck crystal.

“Please. I am unwell.”

He hadn’t tripped over his own feet but somebody else’s. Somebody’s long, slender, pale bare feet, protruding onto the path at the ends of skinny, bony bare legs. In mid-April, it was still too chilly to go bare legged, barefoot. The rest of the person, from the knees up, lay hidden by leaf and shadow.

“Who?”

“If I might…taste it. Please.”

The copper and ionized silver that served his cardiovascular system as iron did his dad’s made Liam’s blood pale, greenish and iridescent, difficult to distinguish against his skin under the dirt on his palm. He hadn’t even noticed the smart. “Please,” the other fairy said again.

“Why?”

One bare foot trembled and then both withdrew. Leaves and shadows shivered. A long moment of near silence almost convinced Liam either to run away (he had never encountered another person like himself) or burrow into the bush.

Eyes. Eyes peering through rustling leaves, huge anime eyes with big black pupils that contracted almost to nothing as the face emerged further into light, irises of two distinct colors, crescents of pale gold framing ellipses of silvery green. They were disproportionate to the rest of the face, if you were used to human features, and didn’t blink for the longest time. A pointed tongue licked thin lips. The fairy said, “Only a taste. Please?”

“Who are you?”

“I became lost, disoriented. Now I believe I am ill. This terrible, terrifying place!” The fairy’s chin moved side to side, a wag so rapid it was over before Liam registered it. The skin around his eyes looked bruised, tinted with green and lavender shadows that stylish girls at Liam’s school would emulate if they could. “I sensed you before you fell, before the…blood. Please.”

At the bridge of the fairy’s nose, the inside ends of his thick sable brows, two long filaments trembled like a butterfly’s antennae or cat’s whiskers, seeking, searching. Frightened and excited, Liam moved closer, and they swivelled toward him, still shivering. First his dads and then Liam himself had always trimmed the errant hairs of his own eyebrows—he hadn’t realized how long they would grow nor that at each tip would sprout a tiny gem like a lustrous pearl. “It’s dirty,” he said, offering his open palm.

The fairy grasped his wrist, the fingers with their extra set of knuckles going all the way around. Liam couldn’t tell whether the strength of the grip was innate or desperation. Eyes widened until they appeared to take up a third of the triangular face, then narrowed as the fairy used Liam’s arm to pull himself out of the bush. Like miniature javelins, his antennae went stiff, straight. Light glimmered within the pointy little pearls. “Thank you,” the fairy murmured, but it sounded like a threat and the small teeth behind his narrow lips looked jagged and very sharp. Scared, Liam tried to pull free but the fairy had him. The thin, pointed, whitish tongue lapped at the dirt and blood on his palm.

It wasn’t like a cat’s tongue, prickly and grating but comforting. Liam didn’t think it was like a dog’s but he didn’t know for sure—Ricky’s dog had been afraid of him, resentful, never volunteered any sort of affection. He felt it wasn’t like a human’s tongue either, which always appeared sloppy with saliva and meaty. He supposed it was like his own—they were the same species—neat and pointed and merely damp rather than moist.

Gradually, the fairy rose to his full height, drawing Liam up with him. He was much taller, taller than Joel or Liam’s dad. Liam didn’t notice when he noticed the fairy was nude, something that possibly meant fairy nudity wasn’t anomalous the way human nudity surely was: Liam had never seen a naked woman, unless she was art, the only fleshly naked man his father, accidental glimpses that seemed to unsettle his dad more than him. The fairy hardly resembled Bryan, who looked human, grown up, but Liam almost saw a resemblance to Joel and other lithe, lanky adolescents always taking their shirts off for no reason at all. But Joel’s body hair looked animal, the fairy’s ornamental; Joel’s muscles decorative, the fairy’s feral.

The likeness of the fairy’s body to his own Liam wasn’t ready to consider.

“You said,” he struggled to say, “just a taste.”

He felt a little pang in his palm as if, out of surprise or pique, the fairy had grazed tender flesh with those savage teeth, but a final lap of the tongue soothed it. “Apologies,” the fairy said, sounding cruel, knowing, again. “It was greatly refreshing.” He appeared healthier, the celadon glaze of his skin now opaque. His grip on Liam’s wrist never slackened. “Now we shall go.”

Flinching, Liam attempted again to reclaim his hand. “Go? I don’t know you—I’m not going anywhere with you.” Liam was inhumanly strong (something he never let the school bullies discover) but the adult fairy stronger: he felt the bones of his wrist rub together in the fairy’s grasp. “Let me go!”

“You do not belong here. It is unwholesome for you.” The fairy seemed to be smiling though his eyes had turned away, his gaze turned inward. “Come, it’s not far to the door. We will take you home.”

Liam knew stories about fairyland. He flashed on Harry Hogan and his pals leering at him—on Joel’s big puppy-dog eyes and eager smile—on how much of the world he’d grown up in made him ill, how much he didn’t fit. On his dad’s face, disappointed and angry and hurt. “Let go of me! This is my home.” Too distracted to think of raising his free hand, he twisted and pulled at the other with all his strength.

“Did you believe yourself a man, poor little fellow?” The fairy did something peculiar with the fingers holding Liam’s wrist and abruptly there was no pain—no feeling at all in the limb. “Come now. Mother wishes to welcome you home.”

He had been scared and ambivalent. The word mother enraged Liam. Without conscious intervention, the fist that still worked came up to sock the fairy’s delicate jaw and then his pretty nose, solid, furious blows saved up for years as if the fairy were Harry taking his taunts one step too far. “I don’t have a mother,” Liam was yelling. “I never had a mother. She abandoned me like I was trash—like shit! Like the sorriest piece of shit on earth!”

It seemed the fairy had never learned to defend himself, nor to fight. Releasing Liam’s useless arm, he quailed back without being able to escape the fist that functioned, although Liam had never learned to fight either. His punches and slaps flew wild, some not hitting at all, but the fairy staggered away, making sad whines and chirps of protest. Iridescent blue-green blood spilled from his broken nose. With the enormous eyes clenched shut, his face looked pinched and incomplete. One antenna had broken, its pearly tip swinging wildly as the fairy stumbled.

Pursuing him, Liam stumbled, too, thrown off by the dead weight of his left arm. The next blow to land, a savage slap to the fairy’s lovely whorled and pointed ear, nearly overbalanced him, while the fairy swivelled and ducked, sobbing hoarsely, wordlessly, turning up his shoulder to deflect another punch. Liam saw the fairy’s wings.

He’d never properly seen his own. It required mirrors, or his dad taking photos, a pastime Liam wasn’t morbid enough to encourage. Anyway, Liam’s wings were barely better than vestigial—he had no control over them, useless stumpy appendages of chitin, cartilage, and glassy membrane that chose embarrassing moments to flex. The scholar Bryan occasionally permitted to examine his son opined that they were immature, they would grow and he would grow into them, but nobody knew much about the fairy life cycle and it seemed just as likely inappropriate diet and childhood environment had stunted Liam’s wings.

Folded down his back like quivers of glass arrows, the fairy’s wings extended nearly to his knees, glistening. Even as he wanted to break the fairy’s face or run away, Liam wished to see the wings spread up and out and lift: to see the fairy fly.

But apparently he was too disoriented to think of it, of how easily he might flee Liam’s punishing fist. As he staggered blindly away, the wings bounced and rattled on his back, sounding like distant rain.

Liam lurched after him, panting with fury—too furious to encompass his anger, own it. It had felt good to hit the fairy, good in a despicable way to damage such beauty and cause it pain. It was all mixed up. He’d always believed himself strange, grotesque, ugly—he resembled neither of his handsome dads at all—but he knew the fairy to have been beautiful before Liam broke his nose, knew they looked as like as son and father. He’d often pined to know who he was, how he came to be, but the records of his true parentage were sealed, as far as he knew, and it would hurt his dad, his real dad, if he went digging. Nobody, not even his dad’s professor friend, could tell him (he felt it was could, not would) what it meant to be himself, raised in the human world, a wonder and a freak. All he had was stories, fairy tales.

At the center of the park rose a round hill like an overturned mixing bowl. Its peak stood higher than the crowns of all but the tallest trees so the obelisk honoring the town’s war dead was visible throughout the valley. Over the years, many had believed it to be artificial, remnant of some unknown pre-Columbian culture, but excavation yielded no evidence. The lunatic fringe insisted it was a locus of supernatural influence, a site of magical power. Liam had never noticed anything particularly special about the hill, beyond its oddity. Now they were climbing it, Liam trailing behind the sobbing fairy.

It was not a difficult haul but the fairy was broken and Liam’s dead arm had commenced shooting pings of sensation from wrist to shoulder. He teetered every time they hit and fell behind. In a way, he feared reaching the crown of the hill: there were sure to be people there—admiring the monument, admiring the view—neighbors and tourists. They would see the naked, wounded fairy, see Liam…. He lagged farther behind.

But the fairy halted, scarcely a third of the way up. Unsteady, he merely stood for a moment, but then he looked back over his shoulder, eyes vast, and saw Liam still toiling after. The fairy shuddered. The long wings trailing between his shoulder blades jittered as muscles jumped, then snapped open. Liam caught his breath. Late-afternoon light trapped in the crystal cells within the venous structure of the upper vanes turned them to liquid gold. Around the outer margins clung scales of dense, textured color like scraps of velvet that held the light and made it their own. Below, the blade-shaped hindwings were all translucent, filmy veils of watery blue and green captured for only an instant within branching and rebranching jade veins.

Turning, the fairy faced Liam, looming above him, facing him down. Sunlight made him solid, intimidating, despite the damage to his nose and the liquid stains of blood on chin and chest. He exposed his teeth, not a smile, and his long fingers flexed.

Liam raised his foot, took another step up the slope. The fairy flinched. Behind him, where a moment before had been only grassy hillside, a door stood up from a slab of silvery, polished granite, its frame carpentered into the air. The fairy’s wings cast powdery stained-glass shadows on planed planks fastened together by intricately carved bracing.

Liam ventured another step. The fairy moaned and shut his eyes for an instant. As the door began slowly to open behind him, he fluttered forward and down, horror implicit in every tentative step, head half turned as he watched to ensure the door didn’t catch wings or heels.

Liam grunted, a hard sound in his throat. He had to—what? Punish the fairy more? Prevent his escape? Follow him?

The door stood wide. Frozen like prey, eyes as wide and deep as eternity, the fairy gave Liam a last stricken glance. “You might—” the fairy bleated. His wings beat hard—a noise like approaching thunder and a gale of turbulence bearing scents that made Liam’s heart contract—and whatever else the fairy said was lost as slender toes scrabbled to maintain his balance even as they lifted from the grass.

Liam rushed the last few yards but the fairy was already aloft, suspended from glistening wings like a slaughtered lamb from the cruel iron hook between its shoulders. Leaping, Liam swatted at the sky. Beating wings drunkenly swooped the fairy higher, farther, away. His limbs dangled like a mosquito’s, paddling the air. A drop of cooling fairy blood splatted on Liam’s cheek. Clumsy in the air, the fairy made a slow half circle out over the leafy park, high above Liam sprawled weeping on the stone sill of the magical door, and then half closed his upper wings and darted, a stooping hawkmoth, over Liam and under the lintel.

Staring at endless blue sky through veils of tears, Liam hyperventilated. The wind through the door, brushing coolly over his face, smelled—tasted—like no air he had ever breathed. He had never before been offered fresh air to breathe. Whimpering, he hauled himself to his knees, grabbed the frame of the door to drag himself upright. Shivering against feelings he couldn’t name, he peered through the portal.

A twilight that never ended. White and amethyst and garnet stars sequinned the indigo horizons. It seemed there must be a full moon somewhere but Liam couldn’t find it. Below him fell the spreading skirts of an everlasting antique mountain velveted with forest and meadow every deep shade of green and purple.

Something like a hawk or dragonfly or immense firefly fleeted up a shallow crevasse toward the door, toward Liam, trailing flickering sparks as if the air were so thick with oxygen and vitality that it ignited at the strike of wings. Liam wondered if it was the fairy, his fairy, but then he saw there were many more, flitting or swooping or fluttering above the landscape and high in the sky, each with its comet-tail of sparks. Breath filled his lungs with immeasurable silence and sorrow and he felt the stumps of his own wings fidget, struggling against the weight of shirt, jacket, backpack.

Unthinking, he shrugged the pack off, unhearing, heard it thud to the grass behind him and tumble a way down the hill. Still he stared. His vision was sharpening. He believed he saw a great river wind across a broad plain and a strange obsidian city or palace erupt where river purled into unlimited ocean. He believed he saw a mountain sculpted in the likeness of a sitting leopard, snarling silently at the fairies that circled its head, spritely and unconcerned. He saw a rocky bluff upon which stood the disembodied stone heads of a hundred titanic kings and queens, their blind eyes weeping. His lungs were so full of the air of fairyland he could no longer breathe.

Flexing, writhing, his wings tore through the fabric of shirt and jacket. They vibrated with such intensity that he moaned. If he chose to step across the threshold, he might take nothing of the world he knew with him. Frantic, he ripped the noisome rags from his shoulders and arms. A shred of t-shirt drifted through the door and burst into blue flame before it touched ground. He reached for the brass buckle of his belt.

Unfastening it, his hand brushed the oblong lump of the phone in his pocket. If he were to set a single foot on the soil of fairyland, only for an instant, when he turned back the world he knew would have changed. He would no longer know it. Climate and weather patterns would have shifted in ways no scientist could predict. The sea would have risen to make an island of the distant, enchanted city where his dad #2 had settled, if not drowned it utterly. People, human people, would be half machine. Harry and Brandon and Tyler, even Joel, would be old, bitter old men if they lived at all. Liam’s dad, Dad #1, the only person in the universe who truly cared about him, would be long dead.

Liam sobbed aloud and inhaled another draft of the intoxicating wind. His wings fluttered with contained longing. The closing door nudged his heel.

Clenching his eyes against further sight of the land that called him, he tumbled out of the door’s way, into sun-warm grass that smelled of sour rags and iron rust and plastic. He coughed and coughed and wept until all that marvellous air had dissipated from his system and all that remained was all he had ever known.

The phone vibrated against his thigh. Flailing, he pulled it out. He was weeping too hard to read the name on the display, couldn’t take in sufficient of the foul air to speak when he opened the phone and lifted it to his ear.

“Liam?” The worry in his dad’s voice would have saddened Liam if he could become any sadder. “Liam, are you there? It’s been almost two hours.”

Liam uttered a croak that was meant to be Dad.

“Liam! What’s wrong? What happened?”

Liam coughed. “Daddy.”

“Babe, what is it? What can I do?”

“Daddy, please. I need you. Please come get me.”

“Where are you, Liam? Are you hurt?”

Everything hurt. “I’m all right. But I just need you so much right now, please. I’m in the park, on the west side of the hill. I love you so much, Daddy.”

“I’ll be there in five minutes. Liam, babe, I was so worried. I love you more than anything ever.”

Liam coughed his voice clear again. “Backatcha, Daddio,” he said, and closed the phone. “So very much.”

Slipping the phone back into his pocket, Liam shivered at the cooling air on his bare torso and felt an unfamiliar tug and pull in the center of his back. Craning to look over his shoulder, he saw the jewelled edges of his open wings, straining to catch a vanished wind.

Copyright © 2010 Alex Jeffers. First published in Icarus: The Magazine of Gay Speculative Fiction, Issue 5, Summer 2010.