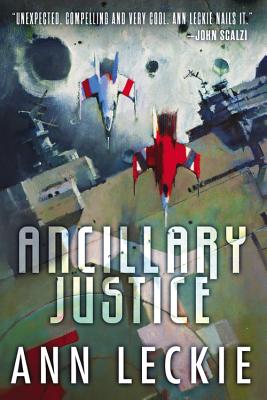

Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie (Orbit, 2013)

Not, let me say flat out, a recommendation to every reader. You’ll have to enjoy and appreciate science fiction. By which I mean real SF, not comforting archetypes and mythic tropes dressed up in flashy magic-tech that reassure you about eternal (Western, Anglo, patriarchal) verities, like, say, Star Wars and its interminable ilk. This is a tremendously disorienting novel—rewardingly, even intoxicatingly so, to my mind, but tastes and expectations differ.

Not, let me say flat out, a recommendation to every reader. You’ll have to enjoy and appreciate science fiction. By which I mean real SF, not comforting archetypes and mythic tropes dressed up in flashy magic-tech that reassure you about eternal (Western, Anglo, patriarchal) verities, like, say, Star Wars and its interminable ilk. This is a tremendously disorienting novel—rewardingly, even intoxicatingly so, to my mind, but tastes and expectations differ.

Full disclosure: In her capacity as editor/publisher of on-line speculative-fiction ’zine GigaNotoSaurus, Ann Leckie has purchased and published two of my stories, “Tattooed Love Boys” (March 2012) and “A Man Not of Canaan” (July 2013). My professional acquaintance with her has been cordial, amiable, and I have tremendous respect for her editorial acumen. I was aware she wrote fiction as well as editing it but had never got around to seeking any of it out. Admittedly, I mightn’t have paid quite so much attention to the pre-publication buzz around Ancillary Justice, her first book, absent that slight connection. But the buzz was sufficiently intriguing for me to put down cash money for a copy, a rare thing these impoverished days. Took me a few weeks to get around to reading it (I’ve been busy. And whatnot), but when I did, bang! all night, one sitting. Within the year, I expect I’ll read it again.

I said disorienting. On the first page of Ancillary Justice, the first-person narrator comes across an injured, unconcscious person on a snowy street of an isolated hamlet on an unimportant planet far from any center of civilization. Whom she recognizes. As an officer she served under. Whom she believed dead. For more than a thousand years. Not much later, we learn she herself has been aware, alive, at least two thousand years.

I call the narrator she. Her native language doesn’t mark gender and Leckie has chosen to translate that language’s ungendered, human third-person pronoun with English’s feminine. The narrator is aware many other languages do mark gender (more insistently than English, some of them, it seems), that in some cultures the distinctions between female and male are as critical as those between human and other. When dealing with people of those cultures, speakers of those languages, she’s always a bit uncertain, wary of misunderstanding or giving offense, because the first question in her mind, meeting a new, clothed person, isn’t man or woman? even when it’s culturally appropriate, and without such gross clues as big bushy beards she doesn’t always guess right. We never learn the narrator’s gender but the injured person, Seivarden Vendaii, also called she throughout, is (so the narrator notes aside) male.

I mentioned the distinction between human and other. Some persons who know the narrator well refer to her as it. Because she isn’t human. She’s a device, a tool, a weapon: an artifical intelligence created and programmed as the brains of an interstellar troop transport. In effect, just as you and I are our bodies as much as we are the mush of grey matter within our skulls, she is the Radchaai vessel Justice of Toren. She is also the troops she transports (though not their officers), all the multiple thousands of her simultaneously—granted the majority are usually in cold storage—which can pass for human among the unwary because their ancillary bodies started out as human corpses. For the purposes of one thread of the novel, the narrator, Justice of Toren, is primarily the ancillary troop decade One Esk, supporting with her multiple bodies and viewpoints her human decade lieutenant in the city of Ors on the recently annexed planet Shis’urna. In another (the novel’s present), she is the single remaining fragment of Justice of Toren after the ship and all its other ancillaries (and human officers, and three instances of the Lord of the Radch) were destroyed in an act of terrible betrayal. In this thread, the isolated ancillary formerly identified as One Esk Nineteen goes by the assumed name Breq and pretends to be an idle, wealthy traveller from the Gerentate, far distant from and not terribly familiar to inhabitants of Radchaai space.

I said three instances of the Lord of the Radch. Analogously to Justice of Toren‘s ancillaries, the millennia-old emperor of the Radch and Radchaai space, Anaander Mianaai, possesses—is embodied by, distributed among—thousands of instances, cloned bodies, the links between them sometimes stretched thin by interstellar distances, sometimes as nearly instantaneous as the nervous impulses between your own brain and fingers, semi-autonomous but all always the same person. As a result of events a thousand years ago (one aspect of which had led Justice of Toren to believe Seivarden Vendaii dead), Anaander Mianaii is clandestinely at war with herself.

Confused yet? It’s all handled much more deftly and delicately than I’m doing here, but if you aren’t willing to be confused, immersed in confusion—the plot is nearly as tangled as the setting—Ancillary Justice is probably not for you. Through much of the novel Justice of Toren/One Esk/Breq’s voice is peculiarly alienating, chilly, inhuman, as it would have to be, given what she is. I found that invigorating but YMMV, as they say. One review I’ve run into felt Leckie’s treatment of gender and unconventional use of pronouns were obtrusive, getting in the way of all the admirable goshwow (need I mention that reviewer was male and, so far as I know, straight and cisgender?), whereas I view them as an essential part of Leckie’s narrative strategy. It seems to me Leckie has been more clever about pronouns than Ursula K. LeGuin in The Left Hand of Darkness and more thoughtful than Samuel R. Delany in Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand, and I believe those two novels to be nearly perfect.

Ancillary Justice, I think, is not quite nearly perfect, but damn, is it exciting—sweeping and intimate at once, thrilling and intelligent, vivid, challenging, strange, affecting, painstaking, both intelligent and clever. There’s an old saw, usually attributed to the late Terry Carr: the Golden Age of SF is twelve. It’s funny because it’s half true. You fall in love with Andre Norton (raises hand) or Star Wars (drops hand real fast) at twelve, but then—whether or not you grow up—you want more. Ancillary Justice is more. (I’m not a big fan of the cover, though.)