So soon after “Liam and the Changelings,” I honestly did not intend the next project I worked on, leave alone completed, to be the fifth tale of Liam Shea. I had something else in mind, a story from the very early history of the Kandadal’s world. But my lizard brain has its own priorities, apparently.

Liam #6, which will be titled “Liam and the Pornographer” unless lizard brain changes its mind, is already bubbling away, friskily, in the Cretaceous swamps.

Liam and the Coward

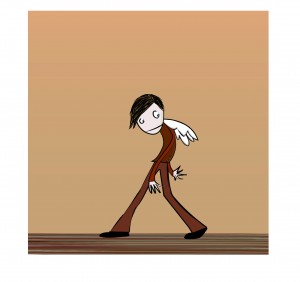

Exhilarated, Liam plunged through the outliers of the oncoming nor’easter, dancing with the gusts and surges. Wind and freezing rain had long since stripped off the last tatters of the glamor he’d worn on the streets of Boston that made him look clothed, human, and older than seventeen and a half. The breath of fairyland, its wild fragrance and flavor, still percolated in his lungs, beat in his blood, helping him forget the manufactured stenches of the city, though once again he had not passed through that door. His dad was expecting him.

He’d been flying high since taking off from the roof deck of Olivia’s building, tracking an uncanny homing beacon. Just because he felt like it, he’d circled the Pru twice, daring early diners at the Top of the Hub to spot the fairy flitting by seven hundred and fifty feet above nearly empty streets—but the restaurant was probably deserted too, the whole city shutting down ahead of the blizzard. Now, two and a half hours later, he was nearly home and the storm was just about on top of him.

The next gust tried to batter him down and he allowed it, diving through wet cloud prickly with ice crystals. Freezing rain and sleet had been left far behind: now it was snow. Heavy, enveloping, hissing snow, veils and whipping curtains like frozen white velvet blown to frenzy. His own body heat and the swift thrashing of his wings prevented it sticking—his inhuman senses made up for snow blindness—he flattened out to a glide ten feet above the obelisk atop the pudding-bowl hill.

For no reason at all, it occurred to Liam he didn’t know the hill’s name. It was just the hill in his hometown park, on the slopes of which, through a magical door, he’d first glimpsed fairyland.

For no good reason, he felt abruptly weary. Battling the storm was no longer thrilling, just a chore he needed to accomplish. The naïve little kid who’d rejected the blandishments of the only other fairy he’d ever met, who’d refused to pass through that door, was nobody to him. An incomprehensible, ignorant, immature stranger. Not that he wouldn’t make the same decision today.

Had made the same decision today. Startling tears froze crystal lenses on his corneas that shattered when he blinked. Olivia’s warning had been oblique, oracular, when she welcomed him again into her cluttered apartment, but when she said, “Remember your promise,” Liam knew what she meant. She said it every time. Before the visit degenerated into sex as it did every time, she taught him a few more cantrips recollected from her long youth in the place he’d never been, told him a few stories. Ugly stories, though she didn’t seem to view them that way. Knowing she’d spent more than a mortal woman’s lifetime traded from one fairy ráth or dún to the next distressed Olivia far less than it did Liam: her worldview was more fairylike than his, who was a fairy.

She’d died pegging him, him with his ass up and five inches of borosilicate glass punching his innards, almost more exquisite in its nerveless rigor than a human cock—uttered a gusty cry as the final orgasm overtook her, then collapsed onto his back, dead weight. Her chin, he thought, had bruised his spine between flailing wings.

Because he was a fairy, after he farted out the dildo and rolled the corpse off his back, he jerked off onto her frozen, startled face, a thing she’d liked him to do. Glistening with lube that didn’t obscure the spiralling cobalt and silver ribbons within the glass, the phallus jutting up from the harness at her crotch appeared incongruous only in the sense that it was shorter and not as thick as the dick in his own hand, and not alive. But neither was Olivia alive. He licked mucilaginous spooge from her face, closing her eyelids with his tongue, and kissed her cooling lips.

Then he spoke the first cantrip Olivia had taught him and opened the door into the unchanging lands. Giving himself no time to think about it, he gathered her corpse into his arms, harness and double-headed dildo and all, and tossed it through, into eternal twilight. Leather, brass hardware, Pyrex vanished in blue flame before the dead woman hit the enchanted ground she’d longed for, and Liam turned away, closed the door before the scavengers of fairyland could gather for the feast.

He spoke another few words of the fairy language to clothe himself in the glamor of Olivia Burgoine’s occasional gentleman caller: a hipster fellow in his mid-twenties with a bushy black beard and ten-gauge jade plugs in both earlobes. In coy acknowledgment of the fairy beneath the glamor, Tinker Bell was inked on his neck in Disney colors, reaching up out of the checked Palestinian kaffiyeh worn as a scarf. He settled the navy-surplus pea coat more comfortably on his shoulders, pulled the knitted watch cap over his ears, peering around the dead woman’s apartment. It struck him there was less stuff than he’d seen on previous visits, as if she’d been getting rid of things in anticipation. Less—still a lot: nothing he’d want for a souvenir even if he were willing to carry it home. When he got home, he’d remember to defriend Olivia’s zombie Facebook profile.

He shrugged—the twenty-something hipster shrugged, pulled on needless imaginary gloves, opened the apartment door. It locked behind him. He passed nobody on his way to the stairwell, nobody on the stairs, jinxed the security on the door to the roof, stepped out into roaring wind and stinging freezing rain. At the roof deck’s edge, he had let his wings break free of the glamor, let the wind take him.

A sudden squall grabbed preoccupied Liam and tossed him against the trunk of a massive sycamore he’d been half aware of swerving to avoid. With a grunted “Shit!” he tumbled and somersaulted into the deep drift at its roots.

Catching his breath, he sprawled in broken snow while more white fluff fell. He heard something, felt something: a groggy sense of something going wrong, swelling concern and alarm—a lightning stab of panic quickly followed by an explosion of blankness. Not his feelings, Liam’s, but somebody’s. Somebody nearby.

Before he knew it, he’d thrashed out of the drift and was fleeting in the direction of somebody, flitting six feet above the snow-obscured path, through the trees, toward the state route that edged one side of the park and led, another half mile on, to his own driveway.

Alighting a few feet from the cockeyed ruby rear lamps of the SUV nose deep in the ditch, he was already muttering cantrips to guard himself against the mechanical behemoth’s steel skin and clothe himself again in glamor. The driver of the ditched vehicle didn’t need to find a wild-eyed naked fairy peering through the window. It was only the driver, Liam already knew, fluttering in and out of consciousness.

Only the driver, strapped into his seat and flattened by the airbag now deflated in his lap, his nose bleeding sluggishly. Liam tapped the glass but there was no response. Jinxing the lock, Liam pulled the door wide and leaned his head in to look. Pulled back right away and slammed the door shut on overheated air reeking of piss and beer and pot.

Harry Hogan. Liam’s ninth-grade nemesis. Harry and his gang of little white boys (token two Cambodians)—they called themselves a posse—who’d chosen the school freak, the fairy, to take out their insecurities on. Liam was never actually afraid of them but it had been politic to permit them to think he was. They’d just find some more defenseless kid to torment. And their jibes did sting, especially when they slagged his ass-munching fudgepacker dad. And their campaign encouraged clueless Joel Berman, already crushing the hell on Liam, in his belief Liam needed protecting, a complication Liam resented. And….

Liam took a breath, held it.

He peered through the glass. The dashboard lights threw distorted illumination. Harry was fully out now. Blood clogged the stubble above his upper lip—the boy was trying to grow a beard. After some prank Liam hadn’t been interested enough to discover the details of, Harry Hogan had been suspended and magically never returned to school. Sent off to boarding school in New Hamster or someplace, somebody said. Without its leader, the posse fell apart and Liam quit paying attention. That was…over two years ago. Somehow Liam had managed never to run into Harry again, though he must come home now and then and the Hogans were the nearest Liam and his dad had to neighbors.

Until now.

Liam told himself some subroutine in the SUV’s silicon brains would have registered the crash and was already broadcasting a mayday. It was probably true: the truck was luxe, looked newer than his dad’s sedan, which had the capability. He told himself that. He told himself he didn’t owe Harry Hogan anything, of all people. He told himself he was cold (he wasn’t, not to notice) and wet and his dad was waiting for him. Harry Hogan could wait for the cops or the fire department. A MassDOT snowplough or some civilian with a phone would have to pass by sooner or later. Harry Hogan could go to hell.

Harry Hogan’s dad would be waiting for his son. By all reports, Mr Hogan was a nastier piece of work than Harry: a Baptist bully who cherry-picked scripture to support loudly proclaimed bigotry—against queers like his neighbor, against uppity women, against science and single mothers and unemployed slackers, against the Muslim socialist in the White House. But a father, who probably—maybe—loved his son, would mourn him if Harry froze to death in a snowdrift off the highway.

Yanking the SUV’s door open again, Liam reached over Harry’s knees to turn off the ignition, hit the hazard-flashers switch, and jerk the shifter into Park. As the dash lights dimmed, he breathed a fairy word into Harry’s blood-rimed nostrils to put him further under and unlatched the belts strapping him down. Harry’s dead weight put up an inert struggle against being wrestled out of the truck but Liam managed it. Surprisingly, Harry seemed to be much shorter than Liam, as though adolescent growth spurts had passed him by.

Now what? The snow had blown up into a proper blizzard. Liam couldn’t see as far as the rear of the SUV. Even with the wind the air wasn’t especially cold, just above freezing probably, but Liam could feel the burden in his embrace chilling fast. Harry wasn’t dressed for the weather and his pants were soaked where he’d pissed himself. Get him out of the storm, into shelter. The Hogans’ house wasn’t much farther away than his own but Liam couldn’t imagine how to explain delivering incapacitated Harry to his family without a car. Home, then.

Tightening his grip around Harry’s back, Liam sliced his wings through illusory shirt, sweater, and pea coat, and took off. Harry’s flopping legs threw off his balance, made him clumsy, but the boy’s unconscious weight wasn’t a problem. He jumped the canted SUV with its vainly blinking flashers and flew into the woods of his dad’s property, gaining height between the trees until he was above them, aiming like a crow toward his own house.

When he reached it, the house was all lit up inside and out, glowing within a dome of blowing snow: worried dad providing a beacon for roaming son no matter how many times Liam told him it wasn’t necessary. He lighted on the front steps—Harry’s feet thumped on the wood in two distinct beats—and used his elbow to ring the bell.

He was trying to hump Harry into a better position when a shadow darkened the front door’s sidelight and Liam remembered he didn’t look like himself. He spoke a syllable as the door began to open.

“Hell—uh…. Liam?” his dad said. The beard must have unravelled then, at least.

“Accident on the road,” Liam said in a rush. “Don’t think he’s injured, just knocked out, but I couldn’t leave him to freeze.”

Throwing the door wide, Bryan barked, “In!” and Liam dragged Harry past him into the warmth and light. “Living room for now, until you get those boots off. What’s that on your neck?”

It took two more steps to shake off the last of the glamor, including offensive boots and that (the Tinker Bell tattoo), another twelve to dump the unconscious lump of Harry on the couch. Liam turned to face his dad.

Bryan’s cheeks went red and he lifted his eyes to the ceiling. “Gah,” he blurted. “Go put some clothes on. I’ve got a—well, a guest. In the kitchen. I’ll check this guy out. Go get dressed.”

“He pissed himself,” Liam said levelly, “just so you know.”

Flying in the house was discouraged but Liam flirted his wings and took off, zooming into the hallway and up the stairs to his bedroom for clothes. It took maybe six minutes but when he pattered downstairs again on his own two feet, decent, it was Harry Hogan who was nude, stretched out full length on the sofa. Full length wasn’t very long: five foot four? five five? A man, a fully dressed stranger, knelt at his side, running his hands over Harry’s arms and torso.

Liam looked for his father. Bryan stood over the pile of Harry’s discarded clothes, an open wallet in his hand. He noticed Liam, said, “Henry Hogan?” in a tone that meant he remembered very well who Harry was, then glanced at the kneeling stranger. “Alasdair’s a nurse. I asked him to look over your stray pup.”

The man had started to turn but Liam bulled in. “Yeah, when I realized who he was I almost left him there. But the road hadn’t been ploughed yet—who knows when anybody would pass by. Alasdair?”

“Alasdair Sterling,” the stranger said, wide eyed, as if he’d never seen a fairy in blue jeans before. “You must be Liam.”

“Pleased to meet you,” said Liam, unsure if he was. “And that’s Harry on the sofa. Old enemy of mine. Find anything broken?”

“Nope.” Alasdair rose to his feet. “Not even his nose.”

“That was the airbag.”

“I’d like a doctor to check him out, of course, but I wouldn’t say it’s urgent. The storm and…maybe give him a chance to, uh, metabolize, uh, illicit substances and take a shower.” Blush mottling fair cheeks, Alasdair looked down at Harry again. “I’m concerned, though, that he didn’t wake while I was handling him.”

“Sorry, that was me.” Liam started toward the sofa and Alasdair moved aside with a jerk—not quite panic: he had a slight limp. “Didn’t want him freaking out in midair. He was awkward enough to carry conked out.” Alasdair’s eyes went wider still, Liam noted with satisfaction. “Something to cover him up? I wouldn’t be too happy waking up completely bareass surrounded by people with clothes on.”

Leaning over Harry, Liam breathed the anticantrip into his nostrils, turned the breath into the boy’s name. A thought that would have been inconceivable in freshman year presented itself: He’s good looking. Fine looking. Trim, tasty little otter. He glanced at Harry’s crotch just before his dad dropped a Hudson’s Bay blanket over his lower half. Promising dick. “Harry. You were in an accident but you’re safe now. Wake up, Harry.”

A flake of dried blood cracked off the rim of one nostril when it flared. Harry clenched his eyelids, didn’t open them, grunted. “Wha’ happened?” His breath was bitter with beer over the sickly sweetness of weed.

Liam perched on the very edge of the sofa cushion. “You were driving—shouldn’t have been driving drunk, you know, especially in a blizzard—and went off the road. I happened by. Didn’t have a phone, couldn’t leave you to freeze, so I brought you home.”

“Oh, god,” Harry moaned, “oh, god. Did I total it? Dad’ll kill me.”

“I was more concerned about you than the car. I didn’t even look at the front. You hit something hard enough to blow the airbag.”

Harry tightened his eyelids. “Oh, god. He’ll kill me.”

“Don’t worry about it right now. How do you feel?”

“Hurty and…and sleepy. Who are you?”

“You remember me, Harry. You used to say horrible things to me in school. Liam Shea.”

Harry’s eyes burst open and a thin, high noise like squealing tires broke through his teeth. Hitting Liam right between the eyes, the blast of his horror dislodged Liam’s own sense of himself so he too felt terror for an instant. Abruptly Harry was blubbering.

“Sssh.” Liam placed his palm on Harry’s chest, feeling the galloping heart before chilled skin and fine, dense hair. “No worries. No plans to beat you up or anything.” Looking into Harry’s frightened eyes, he tried a smile. “It was a long time ago.”

“I’m sorry!” Harry sobbed.

“Sssh.” Calm down, Liam thought so hard Harry had no choice and his sobbing eased. Liam looked over his shoulder.

Bryan and Alasdair had drawn closer together. This wasn’t the moment to wonder when they’d started seeing each other, if they were seeing other, so Liam merely filed a note to pursue later. “Dad,” he said, “looks like Harry and I have some stuff to talk through. In private maybe?”

Bryan glared. “I have to check dinner. There’s enough for Harry if he wants it.” He touched Alasdair’s arm and the two older men stalked out, Alasdair limping.

Harry snuffled. “Your dad? I said horrible things about him, too.”

“You did. I’m thinking he’s not as over it as I…might be. Look, you want to sit up? This isn’t a comfortable position for me. Sorry about your clothes, by the way. Lack of clothes.”

“My—?” Harry discovered the blanket draped over his hips, pulled it higher.

“The ugly truth is you pissed your pants.”

“Oh, god.”

“And Alasdair, Dad’s friend, he’s a nurse, I guess he needed you undressed anyway to check nothing was broken.”

“Better if it was.” Swinging his blanket-shrouded legs out, Harry sat up. “Can’t even run away without fucking it up,” he said distinctly.

Liam scooched back on the cushion warmed by Harry’s body heat. “Run away?”

“Stole my dad’s car. Wrecked it. Fucked everything up again. Didn’t get even a mile.” Crying again, Harry covered his face with his hands.

This was bad. Harry was a smalltime bully, a bigot and a homophobe, a putrid little toad who stank of piss: Harry was a hot little package of ottery hotness Liam could nearly imagine getting down to business with: Harry was suffering a nervous breakdown before his eyes. This was bad, complicated, incomprehensible. Time to rethink the whole Good Samaritan paradigm.

“Should I have left you to freeze in a wrecked car?”

Behind his hands Harry sniffled.

“Except somebody would have come along and it’d be your dad talking to you now.”

“I’m so sorry!” Harry burst out. “The things I said—egging the other guys on—I was stupid and mean and scared.” He lowered his hands and stared at palms glistening with tears and snot. “Sometimes I think about how disgusting I am and I can’t—I don’t know how to make it right.”

“Harry.” Liam put his own hand on Harry’s blanketed knee. “Everybody, every goddamn person in the world, is a petty, vile little monster in their own way. Nobody’s perfect goodness and light. I—my dad wouldn’t know about the names you called him if I hadn’t got some satisfaction out of telling him, painting you as worse than you ever really were.” Taking a breath, he squeezed the knee. “Here, look, you need to blow your nose and, frankly, you stink. Let’s go upstairs. You can take a shower and I’ll find some clothes for you.”

His voice hollow, Harry said, “I’ve got clothes. In the car. I packed everything—I wasn’t gonna go back.”

“Come on. Get up.” Liam stood. “We’ll worry about your stuff later.”

Compliant, Harry rose. The blanket slithered down his knees, bright stripes pleating and folding as it fell. Liam didn’t permit himself to appreciate the charms presented to him. “Come on. Upstairs.”

Halfway up the stairs ahead of Liam, who was looking anywhere except the tight, furry little butt flexing above him, Harry muttered, “I told my dad—” but didn’t complete the thought.

He’s a righteous bastard fuck? Liam wondered. You wished he was dead? You wished you were dead? There was another wonder he didn’t put into words.

He steered Harry into his bathroom, pointed out the clean towel he could use, and left him to it. In his own room, he said aloud, “Fuck. What the fucking fuck?” His dick was half hard in his pants. That was all kinds of wrong.

I told my dad I’m gay.

I told my dad I like to make the sex with other guys.

I told my dad I’d had a letch for you since ninth grade.

I told my dad I want the fairy next door to pop my ass cherry.

“Shit,” said Liam, groping himself through jeans and broadcloth boxers, staring at nothing: staring at the portrait photograph of his dad’s ex on the wall. Ricky, his dad #2. He hadn’t told either dad he was gay because it wasn’t true. But a hot boy was a hot boy and Harry was a hot boy. Depending on accompanying complications, making it with a hot boy—or girl—who wanted it too had to be an absolute good. He believed that.

Here’s the thing, kiddo, Ricky had said one late-night Skype, the crazy mixed-up heartbreaking thing: sometimes sex is the most powerful force in the universe. But mostly it’s simple entertainment. The dangerous part is when the most powerful force in somebody’s universe is just casual entertainment for the other guy. On the computer screen, with his apartment behind him and the lights of San Francisco in his window, Ricky shook his head. Or girl.

Or fairy, said Liam.

Or girl fairy or boy fairy or whatever kind of fairy. And like—here’s your dad talking—from what I saw last time I was out there, I don’t think you could have a casual fuck with your friend Joel ’cause it’d mean too much to him.

That one I already figured out.

Good boy. Good boy. Certain he was the good boy, Ricky’s dog Rufus scampered to the desk barking, and they had to go walkies right away.

And Liam regarded the sweatpants he’d pulled from the bottom bureau drawer because my real pants sure won’t fit Harry. Fine. Boxer shorts and socks from a higher drawer, t-shirt from a third. The last would be tight because Harry wasn’t scrawny like him but cotton knit stretched and dark green would look nice against Harry’s pale skin and sable hair. Anyway, he’s emotionally fragile right now and it wouldn’t be fair to take advantage of it. If he is gay, which he probably isn’t, or…persuadable. And…what about him, Liam? Maybe he was emotionally fragile and fucked up right now without even knowing it. One of the only two people he’d ever had sex with had died today. While she was fucking him. The other was already dead, his corpse long ago digested and shat out by the carrion eaters of fairyland. “Shit,” Liam said. “Shit fuck piss.”

He carried the clothes to the bathroom. Through the door he heard the shower running so he waited, mind whirring. When the water quit, he pushed the door half open, said brightly, “Clothes!” and deposited them by the sink.

“Hey!” The glass enclosure made Harry’s voice hollow, boomy. “You don’t have to— I mean, you’ve already seen it. Me. All of me.”

Liam came all the way in. He grabbed the towel from the bar and handed it to Harry, who was sliding the glass door aside, looking all the more ottery wet.

Stepping out of the tub, looking right at Liam, Harry said, “I don’t understand why you’re being so nice.”

“I don’t either.” Leaning against the wall, Liam looked at handsome, damp little Harry in the mirror instead of full on. “You were a real shit in ninth grade. But I dunno—maybe you’ve changed? Maybe right now what you need’s somebody being nice.”

“I….” Harry paused with the towel over his head. “I do. I’m sorry. Thank you.”

“Don’t worry about it,” said Liam, self conscious. “I kinda think maybe right now I need to be nice. I guess you’re elected.”

Harry tried to smile. Liam felt the effort, the falsity of it, but then the monotonous drippy undertone of Harry’s misery went sideways and lit up for a moment and Harry said, “No, really, I mean it. Thank you.”

To cover his confusion, his stupid joy, Liam reached, plucked. “Underpants,” he said, holding out the green-and-black-check flannel boxers.

Harry’s smile went wider, realer, as he hung his towel over the bar. “That’s not the underwear I picture a—an elf wearing.”

“Fairy. You can say it, it’s the right word. Elves don’t have wings.”

“You do?”

“How’d you think I got you here?”

“Oh, wow.” The wonder radiating from Harry prickled against Liam’s skin. “Oh, shit, I wish I’d been awake for that.”

Liam looked away while Harry pulled the shorts on. “Anyway, that particular pair I don’t wear. I misread the size buying them—maybe I’ll grow into them one day.”

“They fit me fine.” Harry snapped the elastic to demonstrate.

“We’re not really the same shape, you realize. What kind of underwear does an elf wear?”

Harry’s cheeks flushed. “Oh—like a dance belt, I guess. Because tights. Like a ballet dancer.”

“Not for me, thanks. Here.” Liam handed over the sweatpants.

Just holding them, Harry grinned. “I’ve worn one—it’s not that bad. My school has a dance program. I took a semester to fill the athletic requirement. Intense workout. I was a lousy dancer, though.” His mood darkened again. “Dad was so pissed when he found out.”

“He hit you,” Liam said, his own mood thunderous.

“That’s not why I ran away. Tried to run away. Not the only reason.”

“I don’t like your dad.”

“Funny thing,” said Harry bitterly. “I don’t either.”

The two boys were silent while Harry finished dressing. The green t-shirt was tight and looked good on him, emphasizing trim midsection and round pecs. Perky nipples. Liam swallowed and looked at his feet. “We don’t have to hang out in the bathroom,” he mumbled, turning to the door. “You want dinner?”

“I—I’m not really hungry.”

You don’t want to face probably disapproving adults. “’Sokay, me neither. But I’d better let Dad and Alasdair know. You can wait up here if you want.”

Following Liam into his bedroom, Harry said, “I don’t know what I’m gonna do.”

Liam pivoted and grasped Harry’s shoulders before the other boy could flinch. “You’re going to wait a few minutes while I run downstairs, and then we’ll talk some more and figure something out. I’m sure as hell not planning on sending you back to a bastard who beats his kid. My dad’ll back me up.” He thought Bryan would.

“Oh.” Tears sparkled in the corners of Harry’s eyes.

Holding back his full strength, Liam hugged him. Harry gulped once, twice, and put his own arms around Liam. He felt nice, solid. Not as strong as Liam but strong for a boy his size. His hands felt good on Liam’s back, one under the origami folds of a wing, the other lower. Liam felt his dick acknowledge the good feelings and drew back a little. “Okay?” he asked.

Harry swallowed. “Okay.”

“You wait here.” Liam led him to his reading chair, stood over him as he sat.

“Liam?” It was the first time Harry had spoken the name. “I think I’m still a little high. A cup of coffee would be nice if it isn’t too much trouble.”

“Sure.” Smiling down at him, Liam ruffled his damp hair. “Anything in it?”

Harry smiled tremulously back. “I like it black.”

“I can probably manage that.”

In the hall, out of Harry’s sight, Liam waited a moment. He heard Harry stifle a single sob but his feelings weren’t all misery: Liam sensed relief, comfort, hope, a tickle of potential happiness. Shaking his spinning head, Liam started for the stairs.

Going down, he heard scripted conversation from the living room. Looking in, he saw two nearly movie-star-handsome men all up in each other’s business on the wide TV screen, so close it appeared they were about to kiss. When they did, he snorted in the back of his mind and glanced at the sofa. Bryan and Alasdair weren’t in each other’s business (yet) but they sat side by each, the Hudson’s Bay blanket across both laps, and Alasdair’s arm across the back of the couch was near enough sliding down onto Bryan’s shoulders.

Human senses honed by the contagion of his fairy son’s, maybe, Bryan turned his head. His expression hardly altered when he saw Liam—he licked his lips and returned his attention to the television, leaning forward to snag his wineglass from the coffee table.

So that was how it was. Liam went on to the kitchen. He imagined his dad would follow soon enough.

Two plates covered with cling wrap sat on the counter in the otherwise immaculate kitchen. Liam investigated. Roast chicken—slices of breast and a drumstick each—roasted potatoes and Brussels sprouts, bright green beans, scarlet puddles of some sort of conserve. Breakfast.

After stowing the plates in the fridge, he found his dad standing on the other side of the counter. “Were you going to tell me about your new romance?” Liam asked jovially.

“If it turns into one, you’ll be the third to know.” Bryan placed his hands flat on granite countertop. “We’ve had coffee a couple of times. I ran into him at the market and he mentioned the movie, so I invited him to dinner. I couldn’t let you know—you didn’t take your phone to Boston.”

Liam winced internally. “I won’t be going back.”

“Oh?”

“Olivia—well. She’s dead.”

Bryan’s face was blank. He blinked. “I’m sorry.”

“She wasn’t.” Liam took a step, checked. “Dad, I wasn’t in love with her or anything. She taught me things, important things, stuff I needed to know. About myself. Maybe there was more she could have passed on but I’ll deal.”

“Still.” Bryan lowered his eyes. “I mean, I didn’t know her and didn’t much like what I did know.” She turned you into a different person, Liam heard in his mind’s ear. “But still.”

“Yeah.”

The silence was uncomfortable. Liam gathered breath to tell his dad to go back to Alasdair and the film.

“What about the little turd upstairs?” Bryan said. “I put his clothes in the machine—” he nodded toward the laundry room—“but the shower was going so I didn’t start it.”

“I’ll turn it on. He’s…not a turd. I dunno, maybe boarding school?” Looking away from Bryan’s judgmental gaze, Liam said, “I don’t know the whole story yet but, Dad, his father beats him. Harry was running away.”

Bryan’s hesitation was audible. “I’m sorry to say that doesn’t surprise me, what I know about Sam Hogan. So Harry’s staying?”

“Tonight, for sure.”

“Well, that’s a problem. ’Cause Alasdair’s staying over too. I won’t send him out into a blizzard. We only have one guest room.”

Relieved, Liam smiled to himself. His dad #1—very much unlike #2—was one of those for whom sex was nearly always the most powerful force in the universe. “That’s okay. We’ll deal, Harry and me. It’ll be like a preteen sleepover—I never had one of those.” He raised his eyes. “You two want coffee? I’m making some for Harry. It can be a full pot.”

Bryan’s gaze remained severe. “You make it, we’ll probably drink it. Good night, Liam.”

As he turned, Liam said, “Dad?” and his father paused. “Call me babe like you do.”

Bryan’s sentiment sagged into helpless dad-love but his spine remained straight and he didn’t look back. “G’night, babe.”

“Backatcha, Daddio. Same to Alasdair.”

Coffee didn’t agree with Liam (caffeine, he suspected, hit the fairy metabolism more violently than the human) but he knew how to make it. He ground beans, half decaf, half high-test, and set the machine up, put on the kettle for one of the herb teas his dad thought as flavorful as hot water, went to the laundry room to start the washer. Harry’s insulated duckboots sat on the counter, his wallet sticking out of one.

Back in the kitchen, Liam watched falling, blowing snow form oracular, uninterpretable images beyond the window until the kettle whistled. Passing the living room, a hot mug in either hand, he saw that Alasdair and his dad weren’t romancing each other yet, a hand’s width between them on the sofa, intent on the film.

Upstairs, Harry had fallen asleep in his chair. Liam set the coffee on the table beside it and sat on the edge of the bed with his tea to regard the provoking little fellow. Slack, Harry’s mouth hung half open, making him look stupid but serene. Small as he was, he was grown up, his features strong and distinctive, his beard coming in thick. Liam couldn’t grasp Harry’s dreams: they teased at him from a distance like the voices of faraway childhood.

Like any guy, Harry sprawled with his legs wide. While Liam watched, Harry’s dick firmed up in a somnolent hard-on, stretching grey sweatpants fabric as it rose to vertical and gradually tipped over, pointing toward his open mouth. In an XTube video, Liam would creep between Harry’s thighs to take advantage of it—he felt his own stiffen up a bit—but in his bedroom he just observed, intrigued, until it subsided into an innocuous fold.

“Harry,” Liam said at length, breathing wake up across the space between them.

“Hunh?” Harry’s eyelashes fluttered and he sat up so hard he slipped off the low chair.

Liam was there in an instant to help him up. Like a child, Harry fell against his chest. “Oh, Harry.”

“I thought you were a dream. Did I dream that you don’t hate me?”

“I don’t hate you. Anymore. I made you coffee.”

“You shouldn’t be so nice.”

“I’m going to make you sleep on the sofa downstairs—Alasdair’s taking the guest room. How’s that for not nice?”

Harry rooted his nose into Liam’s chest. “That’s fair,” he said indistinctly. “Liam, I have to tell you things. Things I don’t want to say. Can we turn out the lights?”

Liam could see in the dark, near enough, but Harry didn’t need to know. “Of course we can.”

“Can we sit together? Will—will you hold my hand?”

“Harry, am I your friend?”

“I think so? I hope so.”

“You don’t have to ask. Tell me what you need, I’ll do it.”

“Turn out the lights?”

“Get on the bed, get comfy. I’ll grab your coffee.”

When Harry was settled like a rag doll against the headboard, Liam handed him the mug of coffee. Harry smiled bravely. Liam made sure the door was latched, switched off the overhead lamp, crossed the room for the desk lamp. In the dark, he returned to the bed. “Here I am. Careful while I climb in.” He scooched over until their thighs touched and Harry’s shoulder leaned against his biceps, then groped for Harry’s free hand and squeezed it.

“Don’t say anything, okay? It’s…it’s just hard. Dad—my father, well, you already figured out he hits me. ’Cause I’m little and not manly enough and I don’t always dismiss ideas he disapproves of fast enough or loud enough. I had doubts about scripture for almost ever, also, but I don’t know if he knows that.

“He…interfered with me. As far back as I remember up until I was twelve or so and puberty started happening. Didn’t—didn’t stick his dick in my ass but everything else. My mouth. His mouth. Horrible things I didn’t understand, in the dark, couple times a week. Then I started growing hair around my dick and he stopped. Not the hitting. But I didn’t know any better and I—I missed it.”

Harry took a moment to sip his coffee and tamp down his anguish. Liam was only preventing himself from vibrating with fury and outrage by force of will. He had to keep in the front of his mind how much stronger than Harry he was or he’d crush his friend’s fingers to jelly. Recollecting his own set-aside desire for Harry’s body horrified him.

“Maybe that’s why I was such a shit last years of grade school, first year of high school. ’Cause I needed something I couldn’t have anymore that I hated and that scared me. Anyway, you remember I got suspended halfway through first semester tenth grade? And didn’t come back? The night he told me he was sending me away to boarding school, he came to my room again finally. I was black and blue already from all the hitting since school sent me home but he hit me more, telling me I was evil and sinful and a son who dishonored and shamed his father. That was why I wasn’t getting tall, he said, it was a sign of the devil in me. Then he did stick his dick in my ass.

“I couldn’t fight back. I wanted to but I was so scared and brainwashed and he’s bigger than me. It hurt so bad. I was stupid about what he did before, thinking it was some kind of love I just didn’t understand, but I couldn’t be stupid about this. I knew he hated me, he was raping me because he hated me, because I defied him and offended him just by existing, and I knew I hated him. He owned me, he said, this was a reminder he owned me. Then he said, You ever wonder why you’ve got no brothers or sisters, boy? Because this is how I take your mother. No babies born from anybody’s asshole. And then I knew she knew, which I always thought maybe she did because she’s almost as mean as him.

“He did it again the night before they drove me to my new school in Vermont. So I wouldn’t forget he owned me. And the first night every time I came home, and the last night, and a bunch of nights in between. But—but school was good! He wasn’t there. And I made friends and didn’t get into trouble and my grades weren’t terrible. For a couple of months at a time I could pretend I didn’t have a dad, an evil, hateful dad or any kind of dad at all. And I promised myself, as soon as I turned eighteen and the law wouldn’t agree he owned me, I would run away and never see him, never talk to him, never let him talk to me or touch me ever again.

“Today’s my eighteenth birthday. Yeah, you probably thought I was younger but I got held back in fifth grade. I’ve got some money—my uncle, Mom’s brother, always gave it to me on the sly like he maybe suspected something. Enough for two or three months if I don’t find a job right away. So I knew it was going to be today. Did I look at the weather forecast? No, ’course not.

“This morning, something set him off. I don’t know what, I wasn’t paying attention, some internet article probably. He was stomping around yelling about filthy fags and filthy fag marriage and how they’ve destroyed the moral fiber of this goddamn Christian nation, and I wanted to tell him no gay man or lesbian woman or trans person on earth was as filthy as him. But I didn’t. He yelled about your dad, of course, and his unholy damned freak fairy son, ’cause you’re right nearby and he can’t ever forget it. That’s why I was so freaked when you told me who you were.

“When he calmed down some, he told me happy birthday and gave me my present. Fifty bucks and a six pack of beer. Cheap beer, but I guess it did the job when I drank it later. Then I gave him his present: I stood up and said, Dad, I’ve got something to tell you. I’m gay. And it’s not because of what you did to me, screwing my ass every time you could get your pathetic dick up—or was it Viagra got it up? Always. I’ve always been gay. Since the day I was born. I like guys. For sexytimes. I want to marry a guy someday. A guy. A man. Not a defenseless little boy.

“Which, it’s half true. I’ve never done it with a guy, but I want to, but I’m so screwed up in the head about sex stuff because of him that I know I’m not ready and I’d better not try till I figure things out better. And it’s half true ’cause I like girls, too. I think I do. I mean, some girls make me squirmy the same way some guys do. Maybe I’ll fall in love with a girl and marry her instead of a guy. But I wasn’t going to tell him that part. And by the way, I made sure my mother was there and heard it all.

“He sent me to my room. Like I was a toddler. To wait for my punishment for disrespecting my father and telling unholy lies. So I drank half the six pack and smoked some weed a friend at school gave me until it got dark—storm clouds, dummy!—and then I climbed out the window with the bags I’d already packed and my bank card and his grimy fifty bucks cash and the spare keys to his precious new Lexus. You know what happened after that.”

Harry took two hard swallows of coffee that had to be cold. The second made him choke and cough. Freeing his hand, Liam patted him between the shoulders till the coughing wore the boy out. Then he put all the affection and concern he owned into saying, “Happy eighteenth birthday, Harry. I hope it’s better now than it was this morning.”

“It is! You’re being so kind and you listened to me. I didn’t want to say it but I needed to tell somebody. I needed a friend. I needed somebody to be nice to me, like you said.” Surprising Liam, Harry wasn’t crying. He was manic with relief. “I want to hug you if you wouldn’t mind but there’s this cup in my hand.”

“Give it here,” Liam said, his voice unexpectedly rough. He took the mug and stowed it in the headboard cubby, then sat up and opened his arms wide. “C’mere.”

Harry embraced him so hard it hurt, hands knotted in the small of his back—so hard it was as though Harry possessed a fairy’s strength. “You don’t despise me?” he muttered.

“Despise you? Why?”

“For being weak. For waiting so long. For screwing up my escape.”

“I don’t despise you.”

“You will now.” Without letting go, Harry turned his face away. “Back in ninth grade, one of the reasons I chose you to pick on was I thought you were sexy. Freaky sexy. I wanted to kiss you and—and do other stuff, and that scared me. Bad.”

“No, Harry, that doesn’t make me despise you. It makes me think you were kind of dumb back then, but it makes me like you better now. Because everybody’s kind of dumb in ninth grade but only some people get over it.”

“I still think you’re freaky sexy. Fairy sexy.”

Liam dug his chin into Harry’s shoulder and glowered through the dark at the portrait of Ricky. “I’ll tell you a secret now. Back in ninth grade I didn’t but now, tonight, I think you are just so fucking incredibly hot. Fires of the sun hot.”

Harry reared back. “You like guys too? For sexytimes?”

“Absolutely. I’ve been steaming for you since I saw you laid out unconscious on the couch, all naked and hairy and muscley and so goddamn handsome.”

Harry rolled away. “I’m not handsome.”

“You are. Outside. And inside, I think you’re beautiful. Strong and brave and stubborn and precious.”

“Oh, god. But we’re not going to do anything. Sex, I mean.”

“No.”

“Good. I mean, bad. I want to. Someday?”

“You tell me when you’re ready, I’ll fly to you.”

“Liam.” Harry rolled back. “Show me your wings?”

“I’ll have to turn a light on.”

“Do it.”

“I’ll have to take my shirt off. I don’t have a studly build like you.”

“Do it. Please.”

Liam did it. He got up from the bed and turned on the desk lamp. He faced Harry on the bed before pulling his t-shirt off: folded up, his wings were the opposite of impressive, resembling huge scaly warts between the shoulder blades. Harry didn’t flinch at his boney chest and skinny arms. Liam let the wings unfold at their own pace. When the upper vanes first peeked above his shoulders, Harry inhaled, but they kept rising, expanding, growing stiffer as blood flooded into the veins. Harry’s wonder was life’s blood to Liam. He opened them to their widest display, upper and lower vanes, then turned to show them from the side, from the back, the front again.

“Liam,” said Harry. “Show me everything. All of you. You’ve seen me.”

Liam hesitated. “I’m…I’m hard down there. It happens sometimes, ’cause it’s the same blood that makes the wings stand up. Also ’cause you and your hotness.”

“Something to see. Show me.”

Shy for a wonder, Liam turned his back again. Let Harry see his scrawny ass first. The jeans went down. His stiffie caught in the fly, the boxers were harder. When he was free of everything, he waited a minute before turning, somehow afraid.

Lying on the bed, Harry grinned with satisfaction when he did. “You’re freaky beautiful and freaky sexy and that’s a very nice dick.”

“I liked yours. Haven’t seen it hard, though.”

“You will. Someday.” Harry sighed. “I am now incredibly frustrated and maybe hornier than I’ve ever been in my life, so you’d better get dressed again. And then tell me again how you like me for me, not just my studly build and my dick.”

Liam turned off the lamp and did as he was told in the dark. His hard-on deflated with the folding wings but remained on call. Clothed again—he left the jeans on the floor—he climbed back on the bed and told Harry for ten extremely serious minutes how very much he liked him, everything about him. At one point, Harry said, “I’m going to cry again now,” and Liam, glowing inside with the sense of Harry’s happiness, permitted it. Nothing was said of Harry moving to the living-room sofa. Harry said, “I’m not gonna be able to sleep.”

“You will,” Liam murmured and breathed sleep into his nostrils.

“I wanna see you fly,” Harry mumbled. Liam held him. Harry slept. The snow fell. Liam slept, the fires of the sun in his arms.

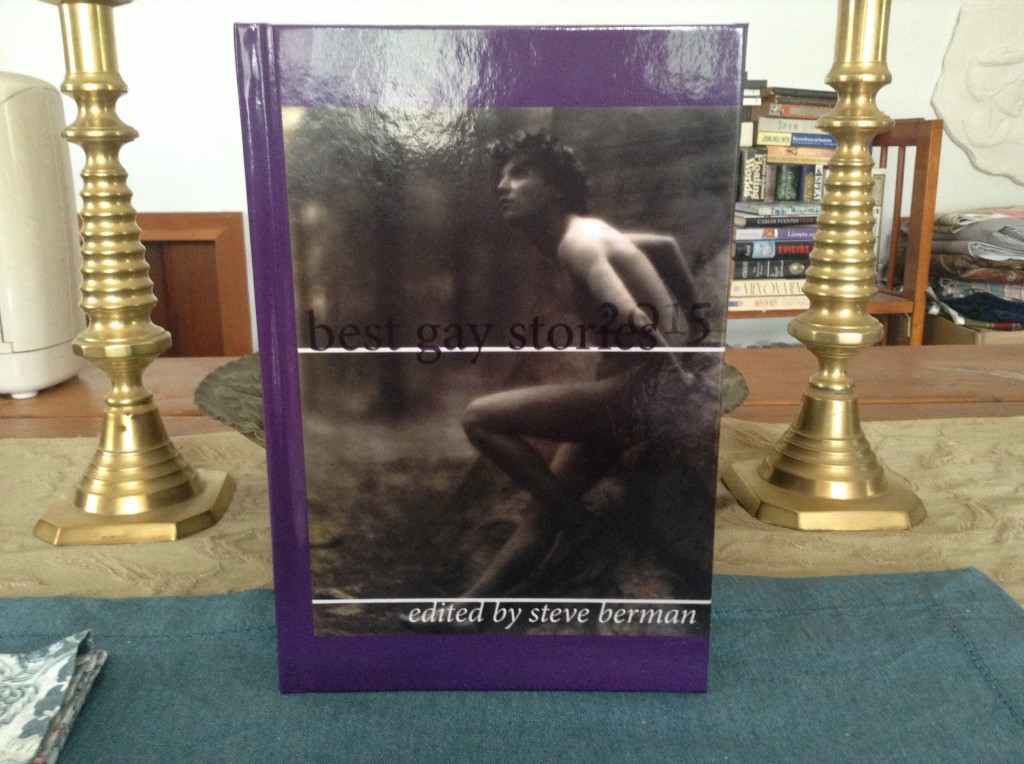

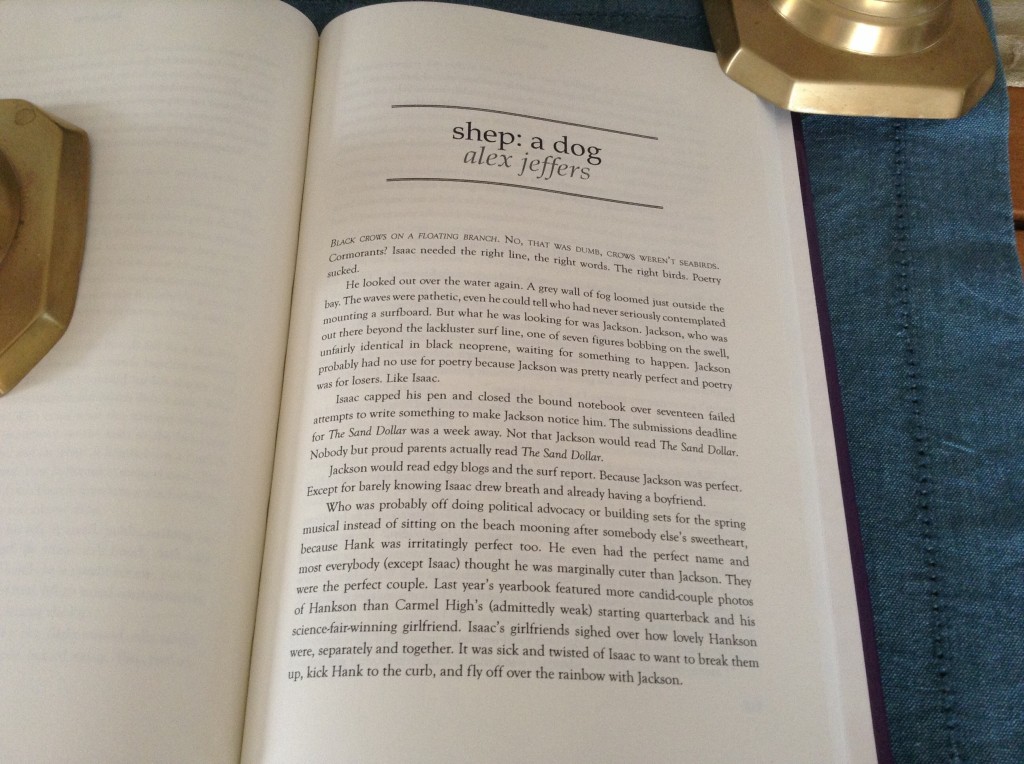

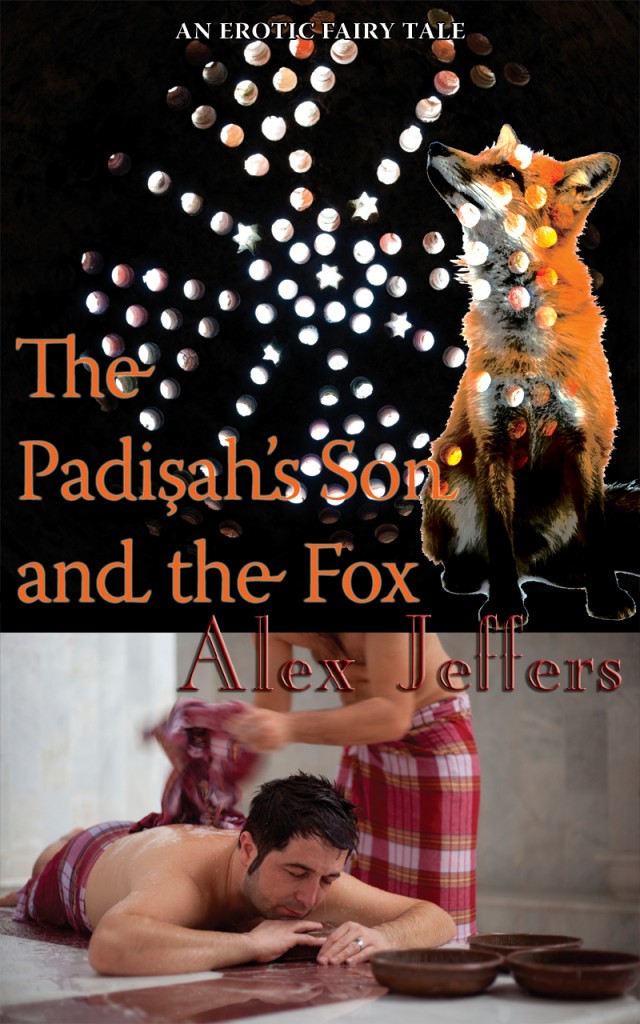

Copyright © 2014 Alex Jeffers. All rights reserved. As a courtesy to the author, please do not reproduce this story without a link back to sentenceandparagraph.com.