I suffered a breakdown, something like a breakdown. Not on account of the traumatic event some people know about (the contrary, doubtless, in some ways), although that was no bloody help whatsoever—some weeks earlier, and then prolonged for nearly three months. Brain chemistry is a tricky thing whether or not mediated by those secretive rulers of the universe, the pharmaceutical-industrial complex (mine is not). I was pretty much incapable of working, neither for myself nor for paying clients. On the internet (where nobody knows you’re a dog) I put up a front, as one does. People who know me may not even have noticed. (I didn’t wish them to.) Then, for reasons having to do with said traumatic event, I lost internet access for some while, making paying work pretty much impossible. I would like to thank my elder brother for a leg up—a couple of legs, monetary and fraternal.

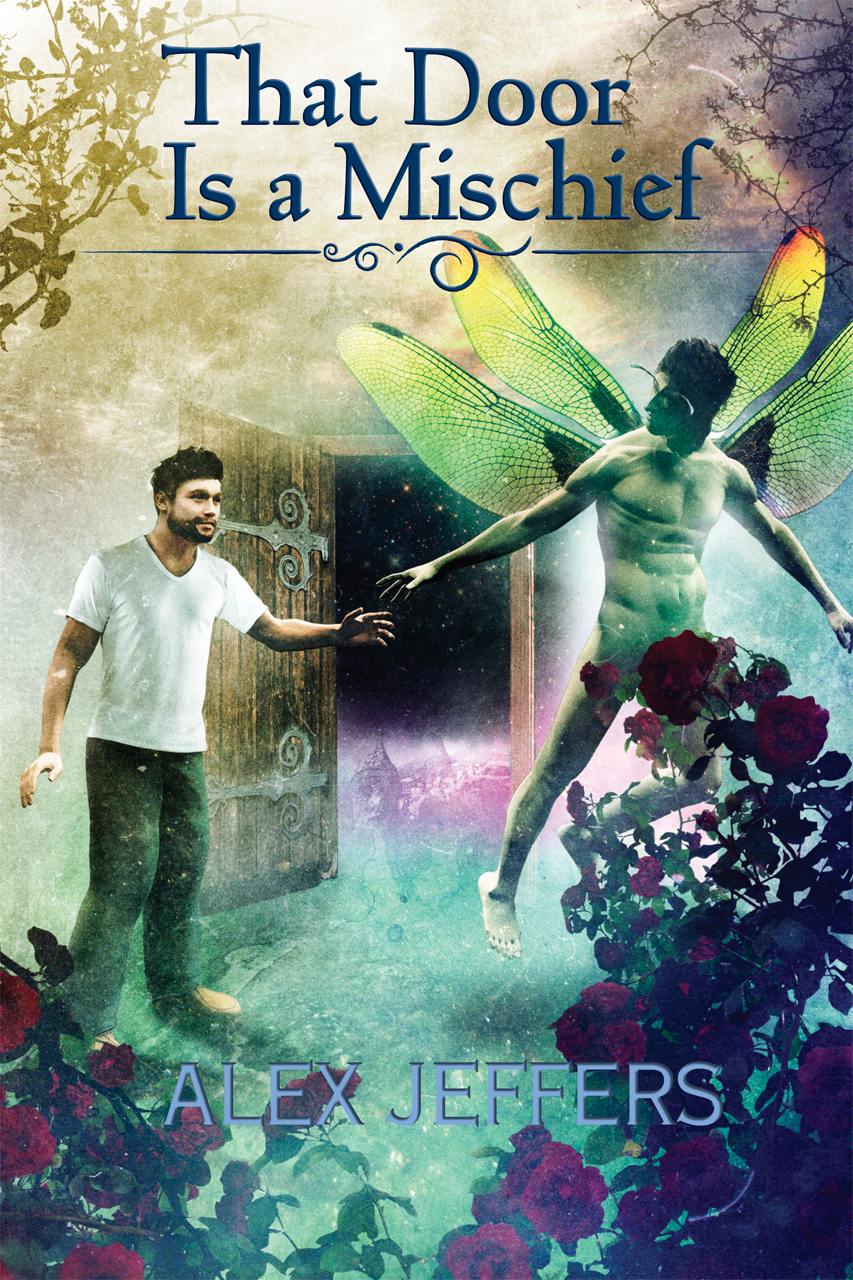

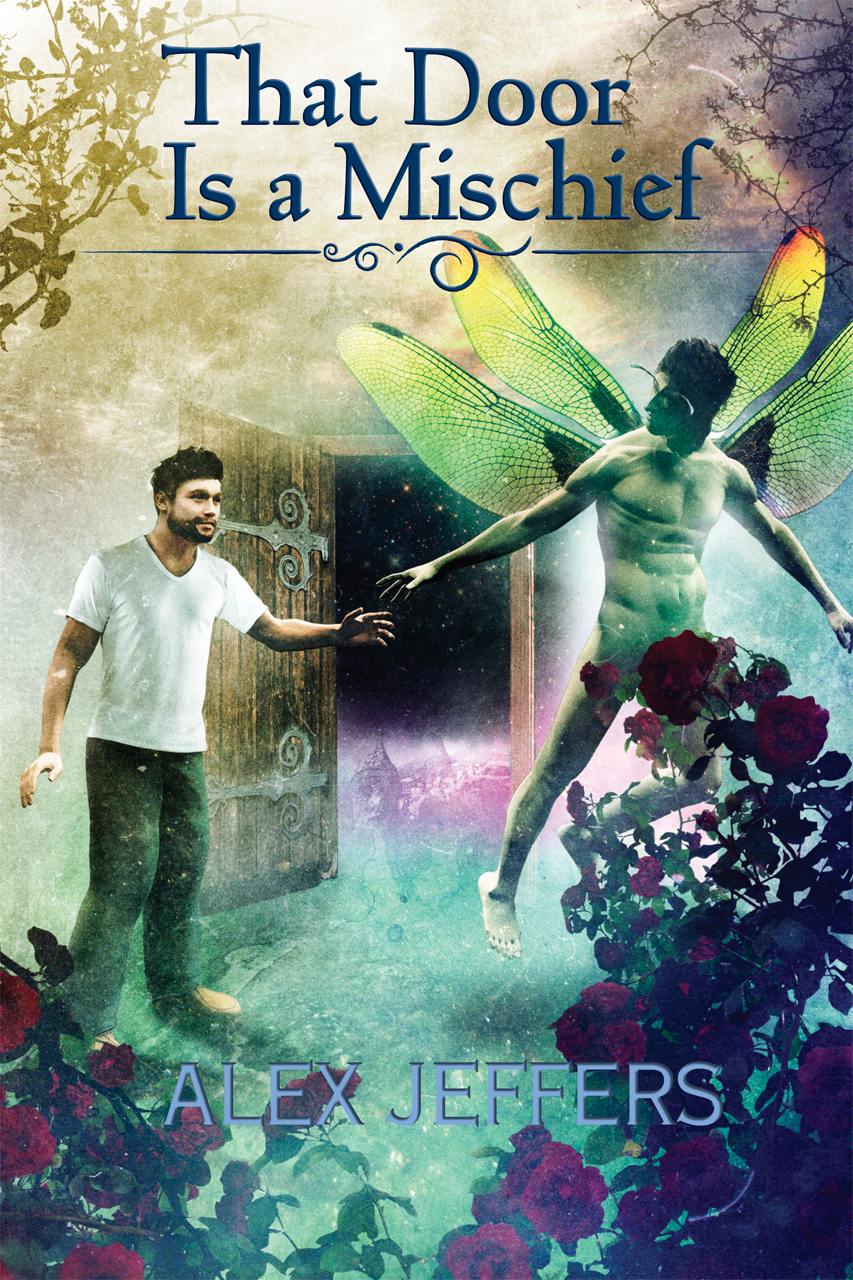

One might think receiving the truly lovely cover art for That Door Is a Mischief from its creator, the estimable Ben Baldwin, early last month would have helped. It was surely a bright moment in a waste of black despair, but moments last only so long. In the aftermath, however, I’m delighted by Ben’s visual imagining of my verbal imaginings, grateful to him for the work and to gentle publisher for commissioning it. Lethe Press will release the novel around about 15 September.

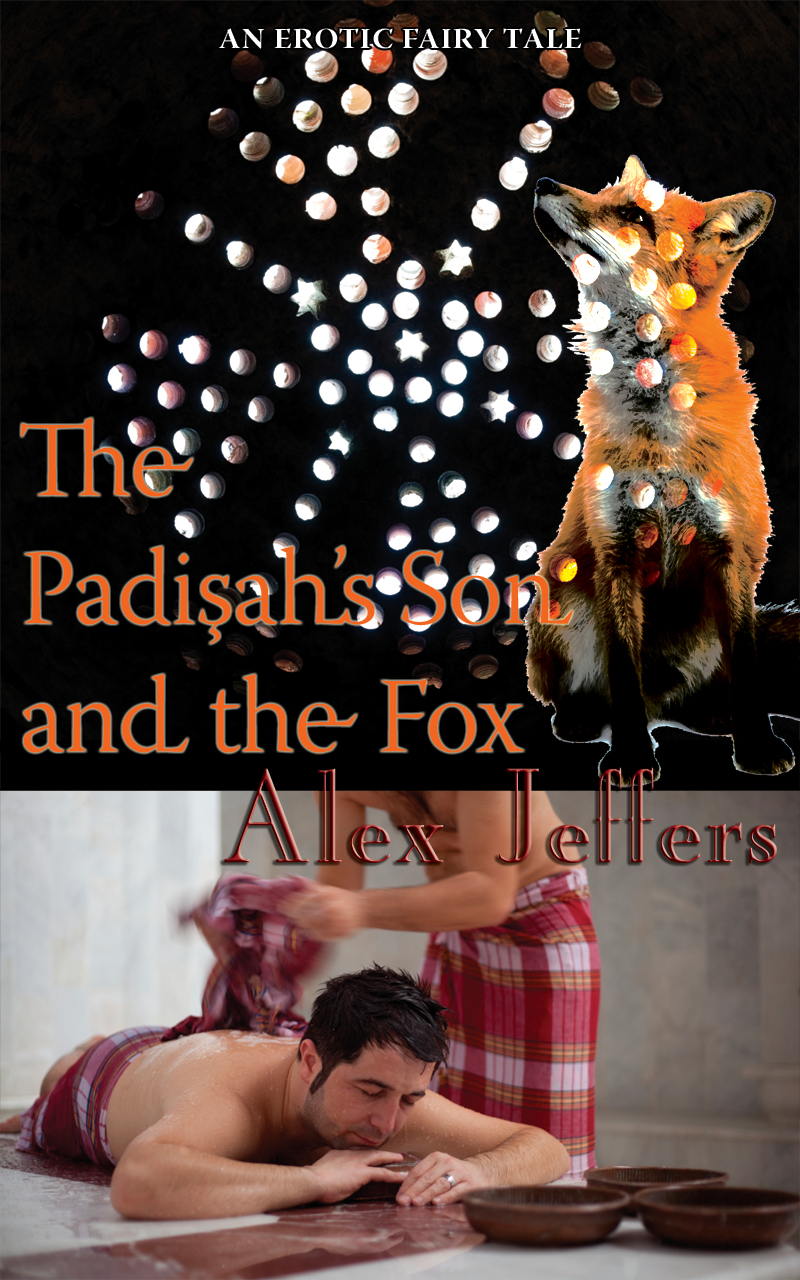

One might think learning The Padişah’s Son and the Fox had won the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Erotica would make everything all better. One would be wrong…even if I didn’t believe the Lammys rather hollow honors. As I do. Nevertheless, I extend my gratitude to the anonymous judging panel, and to Mr Damon Shaw, whose good opinion of the abridged version originally published in 1996 belatedly persuaded me to publish the entire novella.

Toward the end of the horrid interval—just recently, in other words—more serene of mind, properly caffeinated and nicotinated again and still internet-free, I was able to restart the balky writing engine.

Well, first I put some time into revising The Unexpected Thing, which is now about as good as I think I can make it without editorial whips lashing my shoulders. Pretty damn good, that is. I’m now actively seeking representation, if anybody knows a good, aggressive literary agent.

But then I started writing again. I looked over a sputtering constellation of inconsequential fragments committed to pixels and bytes a decade ago, attempted to figure out where I’d meant to go with them. Although I failed in that figuring (just as well), I seem to have come up with a different conceptual schema and to have written the eighty-five-hundred-word first chapter of a new novel. I’m not ready to talk about it much, except to report its working title, Bedtime Stories for the Boy Himself, Perhaps, and the first sentence: He was twenty-two when he realized he was pregnant.

And to quote an essay written by its protagonist in high school, a few years before the novel’s proper start.

Matthew Girard

Senior English, Mr Wallace

18 September 2009

THE SUMMER ANGEL

The first time I saw the angel was two weeks before school got out for the summer. I had gone down to the beach after school—my head was foggy and, as I remember, I was annoyed about something and didn’t want to have anything to do with anybody. There were too many people on the sand so I walked briskly to the end of the beach, below the golf course where the cliffs come down almost to the tide line and there’s no sand anymore, just a shelf of rock with a bunch of boulders up against the cliff.

After walking a way along here, around the first headland, I couldn’t see—or hear—any people, so I sat down on a boulder looking out to sea and smoked a cigarette. I shouldn’t admit that part but if I don’t you’ll be sure to think I was smoking a joint. Because that’s when I saw the angel.

At first I just thought it was a big gull looking for fish, flapping along right above the waves in wide s-curves and figure eights. But as it came closer I saw that its wings were whiter than a gull’s—but not really white, more all colors at once…rainbow colors. White light going through a prism turns to rainbow colors. Its body didn’t really look like a bird’s, either, though I couldn’t tell quite what it did look like yet.

I held very still, not wanting to frighten it away, and it kept getting closer. Finally it alighted about ten feet from me and I could see it wasn’t any kind of bird at all. For one thing, it stood upright and had arms with hands on them, and no tail. I call it an angel because I don’t know what else to call it but it didn’t really look like the Sunday School idea of an angel, being naked and pretty definitely male (I suppose I should say he instead of it). Only about two feet tall, too—I think of angels as being seven and a half or eight feet, or else people size. Anyway, it was definitely too big to be a fairy and its wings were like bird wings, feathered, not dragonfly or moth wings. Maybe it was an extraterrestrial being. Whatever it was, I call it an angel. I said, “Angel,” and held out my hand.

I guess it hadn’t really seen me or thought I was a funny-looking rock, because when I moved and spoke it jumped into the air, flapping its wings madly, and shrieked like a gull. But basically it just seemed to be startled. It settled back down soon enough, fluffing its wings as though it was annoyed, and eyeing me sidelong.

At that distance I couldn’t really make out its face, but later on, as we got to know each other, I discovered the angel’s features revealed just as much expression as a person’s. The expressions—smiling, frowning, etc—were very human, too, and looked rather peculiar on a face the size of a cat’s, pointed at the chin and broad at the temples, with a small nose and mouth and very big, silvery eyes (not as big as a cat’s, though, and with round pupils). I think it may not have been quite adult yet because it had no beard or body hair. Although maybe angels don’t display those masculine characteristics. Its ears were small and round. The hair on its head was short, the same silvery color as its eyes and eyebrows. I wasn’t able to determine if the hair was cut short or if it grew that length naturally. I saw it use its hands several times—it liked to knock mussels off the rocks, pry them open, and pull out the meat, which it ate very neatly, and once I saw it catch a little fish, grabbing it out of the water with both hands—but I never saw it use any kind of tool, and as I said before it wore no clothing. I’m still not sure how intelligent it was. More than a monkey, definitely, but I’m not sure how much more. Eventually it learned to say my name and a few simple words like rock, sea, hand, wing, angel, and boy, but it never got the hang of verbs. I never saw it talking with another angel (it was the only one I encountered, unfortunately), so I don’t know if the sounds it made were language. They had the full complement of vowels and consonants—a few more of the latter than English, I think—and they sounded like language, but more like singing than speech.

But these observations come out of sequence. It took a week or so for it to get accustomed to me, to get over its suspicion and try the treats I brought it. It liked raisins; sunflower seeds and almonds, but not peanuts; rye bread, but not whole wheat or white; M&M’s, plain only, and it disdained the green ones. I’m not sure what else it ate besides mussels and fish. Once when I offered it a bite of my salami and cheese sandwich it got very annoyed, urinated on my head, and flew away shrieking, but the next day things were back to normal. (Angel urine, by the way, is just as nasty as any other kind.)

By about the tenth time I came to see it, the angel had learned my name. I tried to come at the same time every day. I would sit down on my habitual rock and smoke my cigarette. After a little while the angel would come flying in over the water, calling “Matthew! Matthew!” in its high, sweet voice, and land on my knee, sitting astraddle, wings out for balance. If I was still smoking it would be annoyed and yell at me from a distance until I got rid of the butt. When it was feeling particularly affectionate it landed on my head, grabbing my hair in its little hands. I found this disconcerting—especially when it hauled itself hand-over-hand across my scalp until it was hanging head down over my forehead, staring into my eyes and grinning foolishly. It wasn’t as heavy as you’d think, maybe four or five pounds. Probably its bones were hollow. Its skin was quite warm and its heartbeat very fast. Its wings smelled dusty, dry, and its flesh salty, a little like sea water. I am sorry to say it had very bad breath, though its teeth looked healthy if rather yellow. Except for the wings it appeared to be completely mammalian, making it a puzzle how to classify it in biological terms.

I don’t know if one could say I had tamed the angel because I’m not sure if you could ever have called it wild, or even if you’d call it an animal. I kept hoping it might follow me home one evening but no such luck. I’m fairly sure nobody ever saw us together, which is a pity in a way because of course no sane person would ever believe I made friends with an angel this summer. I have one of its long flight feathers, white with an odd prismatic shimmer, but what’s a feather? It never occurred to me until afterward that I should have tried to take a photograph of it. I mean, I always had my phone on me so I could have.

Sometime around the middle of August I went down to the rocks around the headland but the angel didn’t show up. I gave up looking for it after a week or so. I was disappointed that it hadn’t said good-bye.

I’ll say one further thing about Bedtime Stories. A kind reviewer of You Will Meet a Stranger Far from Home said of “Then We Went There” that he wished the story were longer, that I’d explored the world of the Court of the Air more extensively. It occurred to me the other night that, when I composed “Then We Went There,” unconscious memories of those decade-old fragments may have come into play. That is, Matthew Girard uses a similar method to reach his imaginary world as Davey, in the short story, used to stumble from our world into another, and Matthew’s world also features an aerial commonwealth—if not a brutal, all-powerful régime like the Court. So, Benito: Not strictly an extension of or sequel to “Then We Went There” but, when (if) I complete Bedtime Stories, maybe the next-best thing.