Alida Moraes (1888 – 1918) was a Portuguese story writer and poet best known for her posthumously published novelas pequenas (“little novels”). The only book published in her lifetime, a slender volume simply entitled 26 Poemas (26 Poems), appeared in 1910 under the masculine pseudonym Sebastião Preto. In 1916, when the Portuguese Republic declared war against Germany and the Central Powers, she disguised herself as a man and, as Sebastião Preto, joined the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps. Although her body was not recovered and/or identified, she is presumed to have been killed at the Battle of Estaires (9 – 11 April 1918) in French Flanders, when German forces overran the Portuguese lines. In 1920 her family published Flandres, collecting poems in verse and prose sent home in letters and including an often misleading memoir of the poet by her cousin Flávia Ladbourne. Two years later a first, severely bowdlerized volume of eleven Novelas pequenas was released, achieving immediate popularity in Portugal. An English translation appeared in 1926 under the title ‘The Goblin’s Bride’ and Other Modern Fairy Tales; the book has since been translated into fifteen languages and a definitive edition drawn from original manuscripts was issued in Portugal for Moraes’s centennial in 1988.

Biography

Alida Moraes was born 1 January 1888 in Porto, Portugal, the natural daughter of Duarte Sebastião Ladbourne (1873 – 1899), younger son of a port wine shipping dynasty of English origin, and Zubeida Moraes (?1870 – 1888), a laundress, who died giving birth to her. The motherless child was acknowledged by her father’s family, raised among her cousins, but never legitimated. Her early childhood was spent between the Ladbourne properties in Porto and the wine-growing region of Alijó on the Douro River. Moraes was educated by governesses and tutors in company with her cousin Flávia Ladbourne (1887 – 1962), daughter of her father’s eldest brother. She learned English, Castilian, French, and Italian as well as such feminine accomplishments as needlework, watercolor painting, and household management, although her journals reveal impatience with the latter. As she grew older her father, who approved her tomboy qualities, taught her to ride astride and to shoot.

When she was eleven, Duarte Ladbourne was killed, his body found savagely beaten on the Porto waterfront. Municipal police concluded he had been attacked by a gang of ruffians and killed after proving to carry little of value, but the Ladbourne family believed Duarte’s death the responsibility of Diederik Jonckers, a Dutch wine merchant resident in Porto who returned to Amsterdam some weeks later. The motive publicly espoused by the family and their allies was that Duarte had been conducting an affair with Jonckers’s wife, but in Moraes’s journals she declares as a matter of certainty that Jonckers’s family had her father killed to stop an affair with Jonckers himself. Years later she would fictionalize this scenario in two forms, a narrative poem in twenty-six stanzas of ottava rima (1907) and a novela pequena (1911), both entitled “Uma paixão fatal” (“A Fatal Passion”) and neither published until after the death of Flávia Ladbourne, her executrix.

After her father’s death Moraes fell into a deep depression. On the advice of the family doctor she was sent to live at the Ladbourne quinta at Pinhão. She would not return to Porto for nine years, a period she calls in her journals the wild years (os anos selvagens). Her formal education, such as it had ever been, ceased. Nevertheless, within six months she evinced a talent for educating herself, reading through every volume in the quinta’s small library and writing at length about what she had learned in the pages of the journals she had been keeping since childhood. When the library was exhausted, she began requesting books in all five of her languages in monthly letters to her guardian, Duarte’s brother. Few requests were denied: she was not permitted to read Darwin and a request for Oscar Wilde’s The Happy Prince and Other Tales was ignored, although Flávia later procured copies of both The Happy Prince and A House of Pomegranates for her cousin.

As the last titles suggest, she had an interest in fairy tales and folklore. She read Perrault, the Brothers Grimm, the Arabian Nights, Hans Christian Andersen, George MacDonald, among many others, and eventually accumulated the entire run of Andrew Lang’s Coloured Fairy Books. For a period she collected local legends and folk tales from farmwives and vineyard workers, which she recorded meticulously in a separate set of journals. After a year-long lapse in this practice, in 1902 she rediscovered these tales and began to experiment at creating her own, mixing motifs, stock characters, and plotlines from her reading with observations of life at the quinta and around Pinhão and recollections of Porto. Several of the Novelas pequenas are drastically re-imagined and expanded versions of juvenilia from this period.

She also read much verse in all her languages, little of it recent, and wrote a good deal of derivative poetry of her own. Possibly because she had encountered the work of few women poets, she developed a masculine persona for these verses and—after Flávia’s summer sojourn at the quinta in 1904, when the two girls seem to have become lovers—composed passionate lyrics addressed to a distant, unnamed feminine beloved.

Chiefly, however, out of sight of her staid family, between 1899 and 1908 she ran wild. It was then she adopted masculine dress, if not the tailored suits she would affect in her twenties as a scandal about town in Porto and Lisbon. At first she excused the eccentricity on grounds of practicality. Fashions suitable for a bourgeois girl were unsuited to working in the vineyards, as she insisted on doing, to horseback riding, to hunting small game for the larder. For some years she would dress conventionally during family visits and kept her long hair, but at fifteen, enraged when pinned-up braids became tangled in the brush where a wounded pheasant had retreated, she cropped her hair like a boy’s and thereafter wore girl’s clothing only to attend mass with female relations. She paid local men for lessons in knife fighting, variously saying she might need to defend herself from men less understanding or that she planned to exact revenge for her father’s murder. She adopted a mastiff puppy, which she trained up as an attack dog, and for a time took an interest in the locally popular cockfights. Her journals hint that, after the summer of 1904, she made a habit of seducing local girls and women whilst reserving her romantic passion for her cousin Flávia.

She continued to write verse and prose of increasing ambition. On her birthday in 1907 she resolved to compose a memorial to her murdered father, this being the narrative poem “Uma paixão fatal,” which she had completed by late spring. Contemporary scholars have traced explicit parallels between the imagined affair of “Duarte” and “Diederik” and Moraes’s relations with Flávia; interestingly, the “Duarte” figure corresponds with the gentle, civilized Flávia of Moraes’s idealization while “Diederik” resembles the hot-tempered, half-feral poet.

Upon reading the fair copy of “Uma paixão fatal” Moraes sent her, Flávia Ladbourne declared it scandalous, even evil, and begged her cousin to burn the original even as she, Flávia, had burned the copy. This first great argument between the young lovers, conducted entirely through correspondence now lost, bore fruit in the verses that would eventually make up 26 Poemas. Freed from the constraints of narrative—although she retained the magical number 26 for the years of her father’s life—Moraes conflated the Duarte/Diederik affair of her imagination with the Flávia/Alida affair and abstracted both into a sequence of lyrics that chronicle, celebrate, and condemn the passionate romance of an ambiguously male poet-narrator and his bewitching, explicitly female beloved. Moraes was simultaneously composing early versions of several of the original fairy tales that would appear in Novelas pequenas; fantastical elements bleed through from the tales into the 26 Poemas: never-never-land settings, magical beings and creatures, mythic quests.

Journal entries from the period reveal Moraes’s internal conflict over her resolution not to show these verses to Flávia. She did, however, share the tales, generally more to her cousin’s liking. Very much not to Moraes’s liking was the announcement in October 1907 that Flávia’s father, and Flávia herself without great protest, had accepted the suit of one Edwin Montefiore, heir to another port wine house; they would be married in the spring. Moraes raged in her journal, discounting Flávia’s claim she would continue to love her cousin best. The rage spilled over into the penultimate of the 26 Poemas, unanimously considered the strongest.

A month later Duarte’s widowed mother—Alida Moraes’s and Flávia Ladbourne’s grandmother—died in Porto after a brief illness. When her will was read, it transpired she had left a legacy to her favorite son’s bastard daughter that, husbanded with some care, would keep Moraes in independent comfort. The will expressed a hope the young woman would slough her wild ways, conform to polite standards, and marry appropriately; but these were not conditions on the bequest, which was irrevocable.

In January 1908 Moraes returned to Porto “under [her] own steam,” as she wrote—but not to the Ladbourne household. Although her journals take little notice of it, this was a period of trauma and ferment in Portugal. Scarcely a month after Moraes settled in a Porto hotel, in Lisbon the king, Dom Carlos, and his heir apparent, Luis Filipe, were murdered by republican assassins, an event that would lead to the end of the monarchy less than two years later.

In Porto, having outfitted herself with her soon to be notorious bespoke suits, Moraes began the process of reinventing herself as an urban rake. She was taken up by the first of a series of bohemian older women who would shelter her, attempt to satisfy her appetites, and end up both broken hearted and satirized in one of the novelas pequenas. She declined to acknowledge her Ladbourne relatives—to their relief, doubtless—or to attend Flávia’s wedding, although they corresponded every day and engineered clandestine assignations as often as they could, whether in Moraes’s current lodgings or Flávia Ladbourne Montefiore’s new household.

Late that year or early the next, Moraes decided to publish her 26 Poemas after one of her lovers discovered the manuscript and declared it a work of genius. This woman, Rafaela Lazzini (1882 – 1950), a Brazilian heiress and painter whom Moraes calls “the Jaguar” (a onça-pintada) in her journals, created a series of modernist lithographs to illustrate the poems and financed an edition of five hundred copies, which was printed in Lisbon in February 1910, six months after their on-again, off-again affair irretrievably broke down. Lazzini had wished to issue the volume under Moraes’s name but the poet insisted the work had been composed by “the man in my heart,” whom she christened Sebastião Preto. Ultimately, Lazzini chose to have her illustrations credited to the name Moraes had given her, Onça Pintada.

26 Poemas attracted little notice and sold poorly. In the memoir of her cousin she would later write, Flávia Ladbourne laid blame for the volume’s lack of success on unsettled politics: 1910 was the year in which the last Braganza king, Dom Manuel II, “the Unfortunate,” was deposed and the First Republic established. There may be some truth to the claim. At any rate, more than half the edition still remained in rented storage six years later when Moraes resolved to join the Expeditionary Corps, at which time she chose to have them burned. As a consequence the volume is now exceedingly rare; when a copy of the first edition in good condition becomes available the price will be high.

During those early years of the republic Moraes’s dissolute public life belied her writerly industry. Her lovers—including Flávia Ladbourne—complained bitterly when she withdrew from them at intervals to devote herself to her art. She always considered herself a poet first but it appears she wrote little verse during this period. Instead, she revised and re-revised already written novelas—some exist in as many as ten versions—and composed new ones. It is unclear whether or how she intended them to be published or if she wrote the tales strictly for herself and/or Flávia.

In 1915, with the rest of Europe at war though Portugal remained officially neutral, Moraes seduced Beatrix Dumbarton (1897 – 1990), a young Scotswoman serving as governess to the children of a wealthy family of Moraes’s acquaintance. Dumbarton (“the Scottish rose” [a rosa escosesa] in the journals) soon became dangerously obsessive about her lover, often threatening to kill herself should Moraes end the affair. Finding this emotional blackmail unendurable, Moraes absconded from Porto, travelling south to the capital in masculine attire, where she took up residence under her nom-de-plume Sebastião Preto. Back in Porto, Dumbarton did not commit suicide but did suffer a nervous collapse and was kept in seclusion for the remainder of the war. She did not learn of the death of her lover until the publication of Flandres, by which time she had, ironically, met and become intimately involved with Rafaela Lazzini. The two women would remain together until Lazzini’s death in 1950, first in Portugal—Coimbra rather than Porto—then in Lazzini’s birthplace, Rio de Janeiro. In the early 1980s Umberta Freitas, a graduate student at the Pontifical Catholic University in Rio, moved into Dumbarton’s apartment building and befriended the frail, elderly Scotswoman. Freitas later wrote:

The old lady asked me what I studied and I replied, Portuguese literature. “Oh,” she said, “then you will know the great good friend of my youth, Alida—or ‘Sebastião,’ as she liked to be called.”

Freitas earned her doctorate in 1986 on the strength of her dissertation, Sebastião se junta ao exército (Sebastião Joins the Army). After Dumbarton’s death she published a popular biography, A poetisa, a onça-pintada ea rosa (The Poet, the Jaguar, and the Rose, 1992), which, although it inevitably focusses more on Dumbarton and Lazzini’s long life together, remains an essential source on Moraes’s last year in the city of her birth.

It is difficult to determine how well Lisbon was fooled by Moraes’s masculine disguise, or how seriously she herself took it. Julinha Simões of the University of Coimbra speculates in Sebastião, o nome verdadeiro de Alida (Sebastião, Alida’s True Name, 2015) that Moraes was what would now be called a transman; this thesis has been dismissed as special pleading by conservatives, who point out that Simões is herself a transwoman. Certainly Moraes’s contemporaries—and the author herself—did not possess the language to address questions of transgenderism. The evidence of Moraes’s journals is ambiguous. Sometimes “Sebastião” is her father, sometimes her ghostly male twin, sometimes a cruel joke (on the gullible world; on women believing themselves courted by a man; on men troubled by their attraction to another man or, crueler still, on homosexual men discovering an attractive, sympathetic gentleman to be no such thing; on herself), sometimes simply “I.”

At any event, not much more than six months after Moraes established herself in the capital, March 1916, Germany declared war on Portugal as a result of the seizure of thirty-six German and Austro-Hungarian merchant ships in neutral Lisbon. In July of that year, Britain “invited” her old ally to contribute troops to the Triple Entente’s war effort.

Moraes seems scarcely to have noticed the declaration of war—critics have called her “shockingly naïve” about Portuguese and European politics and the war’s background—but when the call for recruits to a new Expeditionary Corps went out she took it as a call to action and an opportunity to prove Sebastião Preto’s worth in an arena more conventionally valued than literature. She prepared fair copies of the poems and stories that best pleased her, had them and a vast trove of rough manuscripts and old journals shipped to Flávia Ladbourne “for safekeeping,” and, as noted above, ordered unsold stock of 26 Poemas destroyed. Then Sebastião Preto volunteered for the Corps.

None of her correspondence thereafter survives, nor any journal she may have kept. Our only sources for Alida Moraes’s last two years are the poems she sent Flávia, posthumously published in Flandres—those Flávia chose to preserve—and Flávia’s memoir published in the same volume, an exercise in mythologizing her deceased cousin and lover.

After some six months training at Tancos, Moraes’s unit was transported to northern France for further training and integration with the British First Army, and by May 1917 had been deployed to the Western Front. Neither Portuguese nor British records take much notice of “Sebastião Preto” so it seems Moraes performed no great feats of battlefield heroism or valor such as earned her fellow private Aníbal Milhais the nickname “Soldado Milhões” (“A soldier as good as a million others”) and the Order of the Tower and Sword. In Sebastião, o nome verdadeiro de Alida, Simões expresses considerable frustration over her inability to track down any surviving veterans of the Expeditionary Corps who remembered the cross-dressed soldier-poet or, indeed, any recollection of Preto/Moraes in published accounts and memoirs. After the Battle of Estaires (AKA the Battle of La Lys), “Preto” was listed as missing, presumed dead.

[…]

Bibliography

- 26 Poemas (as by Sebastião Preto, with illustrations by Onça Pintada [Rafaela Lazzini]), 1910; reissued as by Alida Moraes, sans illustrations, 1923.

- Flandres, com uma memória da autora, 1920

- Novelas pequenas, 1922

- Versos esquecidos (Forgotten Verses), 1964

- Histórias perdidas encontradas (Lost Stories Found), 1978

- Uma paixão fatal e outros escândalos (A Fatal Passion, and Other Scandals), 1978

- Novelas pequenas, uma edição restaurada (A Restored Edition), ed. Julinha Simões, 1988

- Folhas da vida: uma seleção dos jornais (Leaves of life: a selection from the journals), ed. Julinha Simões, forthcoming, 2018

What on earth was that? you may rightly ask.

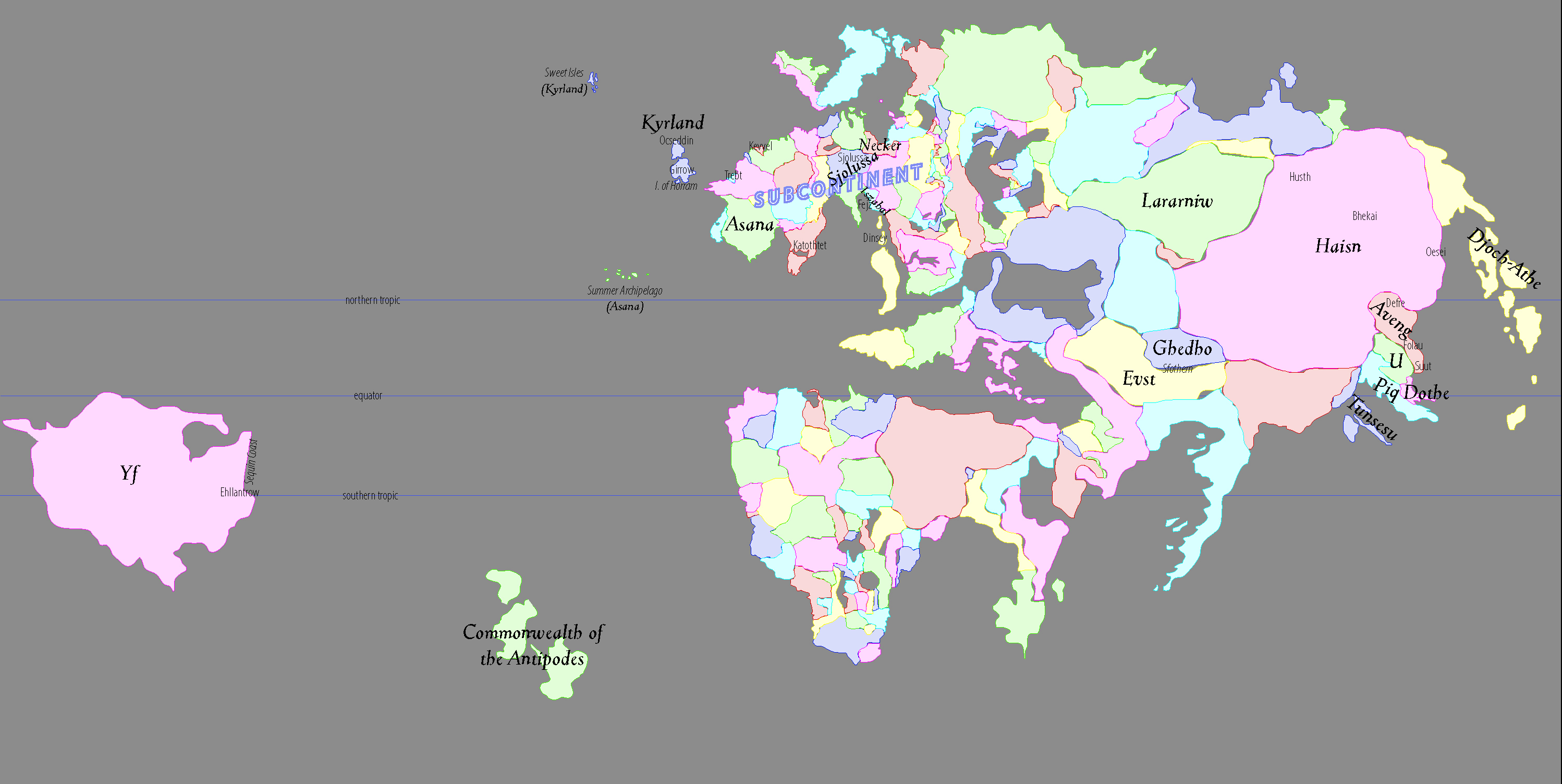

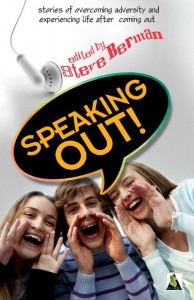

A piece of (invented) historical background for my current work in progress, announced at the end of this entry, the one with the girl protagonist and the working title The Goblin’s Bride (which really needs to change).

As I presently envision the novel, Alida Moraes will not actually appear as a character, although a version of this faux Wikipedia entry may. Nevertheless, her fairy tale known in English as “The Goblin’s Bride” and, especially, the 1999 film based on it, will be of signal importance to the actual characters and the plot and, well, this is the way I work. One of the ways, anyway. At some point in the near future I’ll have to compose a similar entry on that film as well as the text of the fairy tale—Moraes’s original, not the bowdlerized version after which the film’s script was written.

But first I need to complete the second chapter of the main narrative…. Back to work, Jeffers.

Photo by Rob Lorino, layout/typography by me.

Photo by Rob Lorino, layout/typography by me. Oh, and, Lethe Press has posted a freely downloadable PDF copy of

Oh, and, Lethe Press has posted a freely downloadable PDF copy of  While I have yet to see any reviews of The Touch of the Sea, our blessed lord the internet has coughed up several of Boys of Summer:

While I have yet to see any reviews of The Touch of the Sea, our blessed lord the internet has coughed up several of Boys of Summer: In newer news about an older title,

In newer news about an older title,